by Dore Gold

Among the historical

events associated with "Lag Ba'omer," celebrated in the days ahead, is

the Second Jewish Revolt led by Bar Kochba which was a war of national

liberation against the Roman Empire. It mostly took place in Judea,

during the years 132 through 135, some eighty years after the

destruction of the Temple.

At the early stages of

the revolt, Bar Kochba's forces actually defeated whole Roman armies. A

Roman legion that was dispatched from Egypt to help was completely

annihilated by Jewish forces. Bar Kochba fought to liberate Jerusalem

and apparently extended his rule beyond Judea to much of what is today

the territory of Israel. Thousands of coins were issued by his

government celebrating the "Redemption of Israel."

In the modern period,

two schools of thought emerged with respect to his revolt. Israel's

first prime minister, David Ben-Gurion, and most of his generation, saw

in Bar Kochba a heroic leader who could be a source of inspiration for

the youth of Israel who were being asked in 1948 to fight for the

reestablishment of their homeland. On the other side of the political

spectrum, the Revisionists led by Zeev Jabotinsky named their youth

movement after Beitar, where Bar Kochba’s forces were finally defeated

by Rome.

Bar Kochba continued to

be an important symbol for Israel in the years after its independence.

As defense minister, Ben-Gurion authorized the IDF to assist Prof. Yigal

Yadin, the second IDF chief of staff, and his archaeological teams to

uncover artifacts from the Bar Kochba Revolt that were hidden in caves

in the Judean Desert. These included Bar Kochba’s written communications

with his forces and also religious items like tefillin used in daily

prayer. In 1982, Prime Minister Menachem Begin gave a eulogy at the

grave where the ancient bones of the last 25 survivors of the Bar Kochba

Revolt were buried with full military honors.

The second view of Bar

Kochba was represented by Yehoshafat Harkabi, a former head of military

intelligence. In the late 1970s he accused Bar Kochba and his supporters

of bringing national disaster upon the Jewish people by conducting a

war against all odds to defeat the Roman Empire and by relying upon an

"unrealistic assessment of the historical and political circumstances"

they faced.

There is no dispute

that Jewish losses after three years of fighting were staggering.

According to the Roman account by the historian Dio Cassius, written in

the third century, 985 Jewish settlements were destroyed by the end of

the war and 580,000 Jews were killed. After the revolt, Emperor Hadrian

(117-138) forbade Jews from even entering Jerusalem. The leading sage,

Rabbi Akiva, who hailed Bar Kochba as the Messiah, and other members of

the Sanhedrin were tortured and executed by the Romans at the end of the

revolt.

Harkabi influenced a

whole generation of intellectuals and politicians. Israel's former

foreign minister, Shlomo Ben Ami, who was known for his dovish positions

in Israeli-Palestinian negotiations, credits Harkabi with "the erosion

of old mythologies" that could change what he called Israel's "messianic

obsession" with the territories.

A prevalent opinion is

that if the Jews had been content with a mainly spiritual identity,

based on the example of Rabban Yohanan ben Zaccai, who re-built Jewish

life in Yavneh after the destruction of the Temple, the Romans would

have left them alone. But from the year 70, when the Temple was

destroyed, until 132, when the Bar Kochba Revolt began, there was

growing evidence of a renewed Roman enmity against the Jews,

particularly in Judea, but also in the communities of the Diaspora. The

Yavneh option did not appear to be any longer realistic to many at the

time. It was notable that the Jews were far more united behind Bar

Kochba in 132 than they were during the earlier revolt in 70.

Under the Emperor

Domitian (81-96), Roman armies hunted down any potential Jewish leaders

who were descended from the House of David. From 115 to 117, under the

Emperor Trajan (98-117), Roman forces massacred Jewish populations in

what is today Iraq as well as in Egypt, Cyrenaica (Libya), and Cyprus.

Learning the lessons of these wars in the Diaspora, the Jews in Judea

apparently began preparing for another round with Rome, by building

fortifications and escape routes to caves near the Dead Sea.

Fifteen years later,

Emperor Hadrian instituted a ban on circumcision. He also planned to

build a temple to the Roman god, Jupiter, on the ruins of the Temple.

Rome sought to crush the national will of the Jewish people by adopting

laws that were intended to destroy the ability of the Jewish people to

remain constituted as a nation. In fact, after the revolt, Hadrian

renamed Judea as Syria-Palestina, to erase the memory of the Jewish

connection to the land.

One of the mysteries of

the Bar Kochba Revolt was why the Roman Empire concentrated such a

massive military force to defeat what was essentially a guerilla army in

a backwater province like Judea. At the height of the war, Hadrian

dedicated no less than 12 legions to his campaign against Bar Kochba;

there were only 28 legions in the entire Roman Empire. During the

previous century, a major revolt in what is today Germany was vanquished

with just three Roman legions.

Hadrian appointed

Julius Severus, the commander of Roman forces in Britain, to take his

own legions to Judea along with units from the Danube provinces.

The reason for Rome

appearing to have decided that it needed to defeat Bar Kochba at all

costs may be linked to the Jewish struggle for freedom having much wider

implications. Dio Cassius, wrote that "many gentiles came to their

aid." The Jews in the Diaspora and some Samaritans, who in the past had a

hostile relationship with the Jews, also joined the rebellion. Dio

Cassius summarized the effects of the revolt, as follows: "the whole

earth, one might almost say, was being stirred over the matter." Clearly

from this perspective, had Bar Kochba succeeded, he could have brought

down the whole Roman Empire, whose vanquished peoples might have arisen

against Rome as well. Hence its determination to do anything possible to

defeat the Second Jewish Revolt.

So how should we relate

today to Bar Kochba? Should he remain as a legendary hero as he was

depicted by Israel’s founders? Prof. Yigal Yadin made the point that it

is hard for us today to judge the wisdom of those who launched a

guerilla war against Rome in 132. The main Roman historian Dio Cassius

lived more than a century later. There was no Josephus witnessing the

Bar Kochba Revolt and writing its history as it occurred the way there

was for the Great Revolt eighty years earlier.

Moreover, there are

serious dangers emanating from misusing the history of the Bar Kochba

Revolt, and its results, to analyze Israel's political options in modern

times. Had the Jewish leadership of the Yishuv in 1948 relied upon the

alternative interpretations of Bar Kochba as a guide, they might not

have declared Israel's independence, fearing the invasion of six Arab

armies (they probably would have invaded anyway, just to grab

territory). Also, Israel would not have launched a preemptive strike in

the 1967 Six-Day War when Egypt, Syria, Jordan and Iraq were massing

their armies along its borders.

Finally, acts of

heroism are not to be evaluated only by the immediate results they

obtain, but rather by the mark in history that they leave and the extent

to which they inspire future generations. If that were not the case,

then the world would have already forgotten the valor of the Spartans

who halted the Persian advance on Greece at Thermopylae, or the bravery

of the Americans at the Alamo, or even the Russians who lost nearly a

million soldiers holding back the Germans at Stalingrad. The fact of the

matter is that Bar Kochba ultimately won the war he launched nearly two

thousand years earlier, for the Jews returned to their land and

re-established Israel, partly inspired by his example, while the

tyrannical regime of the Roman Empire that he fought is no longer.

Dore Gold

Source: http://www.israelhayom.com/site/newsletter_opinion.php?id=4129

Copyright - Original materials copyright (c) by the authors.

Canadians

are on their guard against the growing Islamist threat. After all, the

last month alone brought the Boston Marathon bombing, and arrests in

Canada of suspected Iranian-linked al-Qaeda bomb-plotters targeting

Canada-US passenger train routes. Add to that, repeated stories of

Islamist radicalism in Canadian neighborhoods and young Canadian Muslim

terrorists abroad.

Canadians

are on their guard against the growing Islamist threat. After all, the

last month alone brought the Boston Marathon bombing, and arrests in

Canada of suspected Iranian-linked al-Qaeda bomb-plotters targeting

Canada-US passenger train routes. Add to that, repeated stories of

Islamist radicalism in Canadian neighborhoods and young Canadian Muslim

terrorists abroad. Despite

all this, El-Kassem is making a name for himself in the more gullible

reaches of some interfaith and outreach fringes, and even policing. The

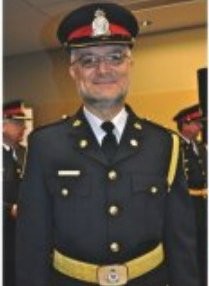

apparently uninformed London police chief, Bradley S. Duncan, rewarded

the imam with – astonishingly – an appointment as police chaplain.

Despite

all this, El-Kassem is making a name for himself in the more gullible

reaches of some interfaith and outreach fringes, and even policing. The

apparently uninformed London police chief, Bradley S. Duncan, rewarded

the imam with – astonishingly – an appointment as police chaplain.