by Amir Taheri

Today, the Tehran "deciders" constitute a small, increasingly isolated minority caught in an imagined past and fearful of the future

- The Chinese found out that producing and exporting goods that people wanted across the globe was easier and more profitable than trying to export a revolution that no one, perhaps apart from a few students in London and Paris, thirsted for.

- The Shah had promised that he would turn Iran into "a second Japan". Rafsanjani promised a "second China."

- Some of Rafsanjani's close associates now tell me that he was "a bit of a coward" and lost his opportunity to do a Deng Xiaoping by being sucked into corrupt business deals. According to them, Rafsanjani didn't realize that one starts making money for himself, his family and his entourage after one has done a Deng Xiaoping, and not before.

- Today, the Tehran "deciders" constitute a small, increasingly isolated minority caught in an imagined past and fearful of the future. Worse still, many "deciders" have already put part of their money abroad, having sent their children to Europe and America. Going through a who-is-who of these "deciders" one is amazed by how many are behaving as carpetbaggers, treating Iran as a land to plunder, sending the proceeds to the West. They cannot produce an Iranian "Deng" because they don't want to create a productive economy; all they are interested in is to get the money and run.

The

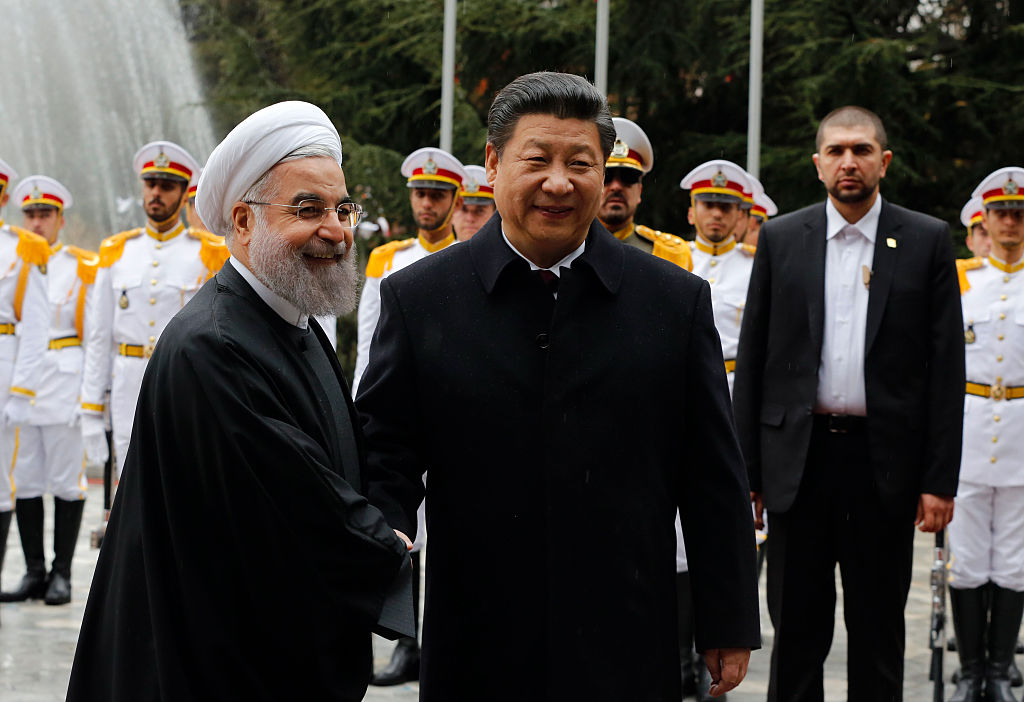

idea of imitating the Chinese model isn't new in Iran. Pictured:

Iranian President Hassan Rouhani shakes hands with Chinese President Xi

Jinping on January 23, 2016 in Tehran. (Photo by STR/AFP via Getty

Images)

|

Could General Qassem Soleimani's dramatic demise provide the shock therapy to persuade those who wield real power in Tehran to admit the failure of a strategy that has led Iran into an impasse? This was the question discussed in a zoom conference with a number of academics from one of Iran's leading universities.

The fact itself that the issue could be debated must be regarded as significant. It indicates the readiness of more and more Iranians to defy the rules of silence imposed by the regime and raise taboo issues more or less openly.

In the course of the discussion one participant drew a parallel between Soleimani's death and that of Marshal Lin Biao, the Chinese Communist defense minister whose demise in an air crash in 1971 opened the way for a radical change of course by Maoist China.

Lin's elimination enabled Chinese reformists, then led by Prime Minister Chou En-lai, to isolate the so-called "Gang of Four" hardliners, led by Mao's wife Jian Qing, and bring the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution to a close as prelude to a historic change of course designed to transform the People's Republic from a vehicle for a revolutionary cause into a normal nation-state. Within a few years, the People's Republic under Deng Xiaoping's leadership was building a capitalist economy with a totalitarian political frame, discarding dreams of "exporting revolution".

Having lost its revolutionary legitimacy, the Chinese Communist regime started building a new source of legitimacy through economic success and the dramatic rise in living standards for hundreds of millions across the country. The Chinese found out that producing and exporting goods that people wanted across the globe was easier and more profitable than trying to export a revolution that no one, perhaps apart from a few students in London and Paris, thirsted for.

However, the parallel isn't exact. Lin was accused of having secret ties with "Imperialism" and plotting a coup against Chairman Mao while Soleimani was regarded as "Supreme Guide" Ali Khamenei's most faithful aide. Lin had a glittering biography, having led the People's Liberation Army in numerous battles to victory with his conquest of Beijing as the final bouquet.

In contrast, even Soleimani's most ardent admirers are unable to name a single battle which he fought, let alone won. Even now his adulators only claim political successes for him, including his supposed success in preventing the fall of Bashar al-Assad in Syria and seizing control of the Lebanese state apparatus through surrogates.

Nevertheless, Soleimani's demise does provide an opportunity for a serious review of Khamenei's policy of "exporting revolution" which has cost Iran astronomical sums and countless lives with not a single country adopting the Khomeinist ideology and system of government.

The idea of imitating the Chinese model isn't new in Iran. It was first raised in 1990 by then President Ali-Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, who went as far as asserting, only half-jokingly, that he would even be prepared to discard the clerical garb to adapt to the modern world. The Shah had promised that he would turn Iran into "a second Japan". Rafsanjani promised a "second China."

The Shah could not fulfill his promise because he was hit by the Islamic Revolution on the road and had to go into exile. Rafsanjani's "second China" also remained a dead dream with the would-be Iranian version of Deng Xiaoping just managing to stay alive and out of jail, barely tolerated by the real "deciders" as an embarrassing uncle.

Some of Rafsanjani's close associates now tell me that he was "a bit of a coward" and lost his opportunity to do a Deng Xiaoping by being sucked into corrupt business deals. According to them, Rafsanjani didn't realize that one starts making money for himself, his family and his entourage after one has done a Deng Xiaoping, and not before. Deng's family, including his daughter, son-in-law and hangers-on made their millions after China had been de-Maoized. In Rafsanjani's case, the millions were made without any attempt at de-Khomeinization.

At the time Rafsanjani played his "China" tune. I argued in several articles that the Deng model was not applicable to the Islamic Republic. In China, Maoism, is quirkiness notwithstanding, was a potent ideology, mixing nationalism, xenophobic resentment, and crude egalitarianism symbolized by the imposition of uniforms and collective production units. In contrast, the Khomeinist ideology was never developed into a coherent narrative while its open hostility to Iranian nationalism gave it an alien aura. Moreover, the Chinese revolution had triumphed after decades of struggle including a huge civil war involving tens of millions on opposite sides.

In contrast, the Khomeinist revolution succeeded in around four months because the Shah, unwilling to order mass repression, decided to abandon power and leave.

There are other differences between Iran today and China in the 1980s. The People's Republic was firmly controlled by the Chinese Communist Party which had at least five million trained and disciplined cadres capable of passing its message to society as a whole and mobilizing support for any change of strategy. The Khomeinist republic has no such structure and its support base, mired in corruption, finds it increasingly hard to communicate with society at large. The mass gatherings that the regime organizes should deceive no one.

Today, the Tehran "deciders" constitute a small, increasingly isolated minority caught in an imagined past and fearful of the future. Worse still, many "deciders" have already put part of their money abroad, having sent their children to Europe and America. Going through a who-is-who of these "deciders" one is amazed by how many are behaving as carpetbaggers, treating Iran as a land to plunder, sending the proceeds to the West. They cannot produce an Iranian "Deng" because they don't want to create a productive economy; all they are interested in is to get the money and run. Nor are they able to build the state institutions needed for a modern economy capable of seeking a credible place in the global market.

The machinery that Deng and his team inherited was certainly repressive and outmoded by the higher international standards. However, within its own paradigms, it worked. In contrast, the Khomeinist republic, though as outmoded and repressive as the Maoist regime, simply doesn't work. Lacking any mechanism for self-reform it resembles the blindfolded horse in ancient mills going round and round, grinding the seeds of a bitter harvest.

This article was originally published by Asharq al-Awsat

Amir Taheri was the executive editor-in-chief of the daily Kayhan in Iran from 1972 to 1979. He has worked at or written for innumerable publications, published eleven books, and has been a columnist for Asharq Al-Awsat since 1987. He is the Chairman of Gatestone Europe.

Source: https://www.gatestoneinstitute.org/15508/iran-chinese-dream

Follow Middle East and Terrorism on Twitter

No comments:

Post a Comment