by Yoav Limor

The fact that Iran could use Hezbollah, its Lebanese proxy, to attack Israel is a given. But how worried should Israel be about Iran's proxy in Yemen? The threat is not imminent but it cannot be discounted.

If there is one thing that is troubling the defense establishment more than the coronavirus these days, it's Iran.

The recent historical progress made in the Middle East peace process is clouded by a cluster of events that have placed the region on edge.

Chief among them is the first anniversary of the assassination of Iranian strongman Gen. Qassem Soleimani, the commander of the Revolutionary Guards' elite Quds Force unit – Tehran's infamous extraterritorial black-ops arm – who was killed in a US drone strike in Iraq on Jan. 3, 2020.

This is compounded by Iran's desire to exact revenge for the assassination of Mohsen Fakhrizadeh, regarded by Western and Israeli intelligence services as the mastermind behind the country's nuclear weapons program; as well as Tehran's desire to retaliate against Israel for its strikes on Iranian assets in Syria.

Israeli defense officials believe that Iran has recognized a window of opportunity during which it could act – the Trump administration is in its last days and the Biden administration has yet to be sworn in, meaning the United States is limited in its ability to act.

This ostensibly presents the ayatollahs' regime with a golden opportunity to retaliate over everything the Trump administration did, from exiting the 2015 nuclear deal and re-imposing economic sanctions that have ravaged its economy, to the killing of Soleimani, which has seriously hindered its export of terrorism, to affording Israel the backing to act nearly freely against Iran across the Middle East.

If this was a case of simple math the Iranians would not hesitate to act. The US has many assets in the Middle East and the Persian Gulf a strike on which would be painful for the United States, and Iran has plenty of proxies in the region – from Hezbollah in Lebanon to the Houthis in Yemen – that are only too eager to do Tehran's bidding.

The reality, however, is more complicated. Iran is wary of an unexpected strike before US President Donald Trump leaves office, and would like to get off on the right foot with the President-elect Joe Biden, who would have to retaliate against any strike on American interests in the region.

The Americans seem more alarmed about the issue and are gearing up for a major Iranian operation. This is why the US has bolstered its troops in the Gulf and has also sent threatening messages to Iran warning the ayatollahs that any strike would meet a devastating response.

Israel, on the other hand, believes that the Iranians would err on the side of caution and that even if they did retaliate, they would opt for a target that would not bring fire and brimstone raining on their heads.

These differences in perception are reasonable, and reflect the difference between in concerns: on a strategic level, Israel wants to ensure the US maintains maximum deterrence vis-à-vis Iran, but at the operational level it has its own issues with which to contend.

Iran has been looking to harm Israel for a while and it has plenty of reasons to use a pretext. Syria, as always, is Iran's go-to theater of operation. It's militias there do its bidding without hesitation, and while they have the manpower and the weapons, they are not sophisticated and the Israeli reaction could prove more than Iran bargains for, as experience has shown.

In 2018 and 2019, Iran mounted several failed attempts to attack Israel from Syria, and paid for it, which is why it is likely to look for another route.

The Houthi rebels in Yemen are likely candidates to assist Iran this time. In many respects, they are similar to Hezbollah, as they would go a long way for Iran as long as it doesn't jeopardize its interests in Yemen.

The Houthis did as much in September 2019, when they claimed responsibility for the drone attacks on two key oil installations in Saudi Arabia – Iran's archenemy in the Gulf. The attack emanated from Iranian soil, but the Houthis were loyal enough to claim it, thus allowing Tehran to maintain deniability.

The concern is they will do the same vis-à-vis Israel. The Israeli defense establishment has been monitoring the Houthis' arsenal buildup, especially given the change in Iranian policy: in the past, Tehran would keep its advanced weapons to itself but recently it has been very generous with giving it to its proxies, particularly the Houthis and Hezbollah.

As part of this policy, Iran has been providing its proxy in Yemen with the same weapons it used to strike Saudi Arabia. This will allow it to attack Israel from outside its territory, using means that greatly challenge the target. Unlike rockets and missiles, the trajectory of which is relatively easy to detect and project, drones, and cruise missiles travel both high and low, making them very difficult to identify, at times until the very moment of impact.

The drone strike in Saudi Arabia prompted the Air Defense Directorate in the Israeli Air Force, as well as the aerospace industries to make adjustments to Israel's detection and interception systems, to better counter these threats.

Yemen is far and so far, it has been something else's problem – the US, the Saudis, the United Arab Emirates – so it has never been a priority for Military Intelligence. This is likely to change, and chances are Israel will ask for help from the US, which keeps close tabs on the southern Arabian Peninsula country.

These efforts should afford Israel enough time to intercept an attack, and given the distance between the countries, interception could involve fighter jets and take place away from Israel's borders.

It is important to stress that by all intelligence assessments, the threat is not imminent. The military seeks to preempt it as well as to generate deterrence. If the Iranians realize Israel is ready to counter them, they may think twice about it – although it is doubtful.

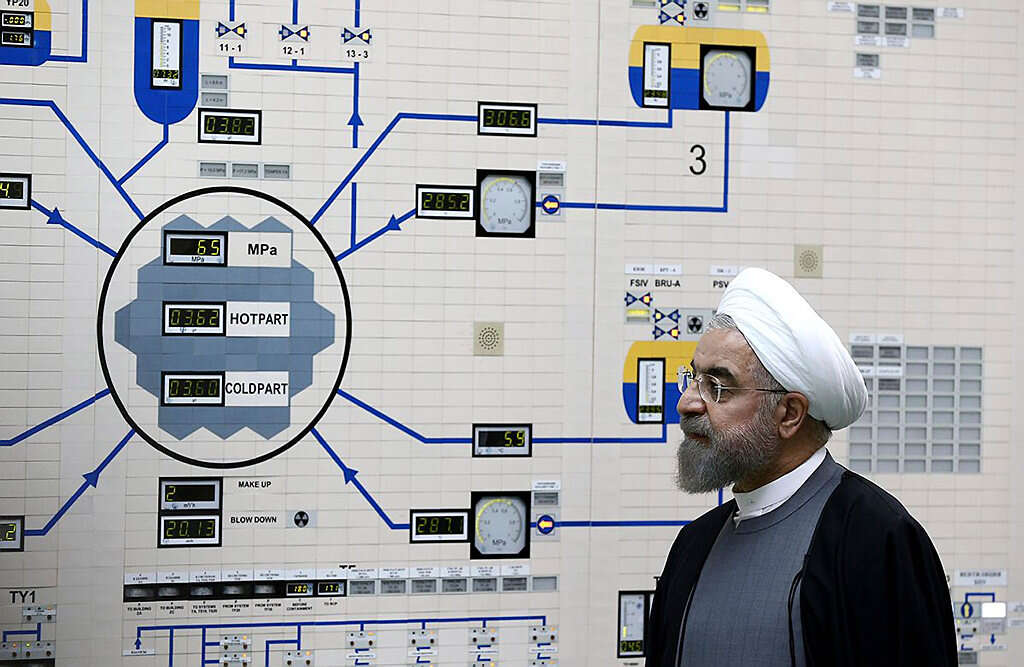

But with all due respect to the Houthis, conventional security threats, and everything that is happening in Syria, Israel is the most profoundly concerned about Iran's nuclear aspirations.

The Islamic republic is a long way away from developing an atomic bomb, but it is slowly and steadily inching toward it. Tehran has been exploiting the fact that the US pulled out of the 2015 nuclear pact to violate the accord time and again and so far, no one has tried to stop it.

This has allowed Iran to accumulate enough low-nuclear bombs. The Iranians have so far been careful not to push uranium enrichment to 20% – despite a parliamentary decision to do so – as they prefer to use that as leverage when they negotiation a new nuclear deal with the US.

Western intelligence officials, as well as their Israeli counterparts, do not believe Iran is about to make a move it would be unable to walk back.

The ayatollahs are already facing several International Atomic Energy Agency investigations over issues discovered after Israel exposed Iran's secret atomic archives in April 2018. As Iran is a member of the UN's nuclear watchdog, it would like to see these cases closed and will most likely throw them in the mix when negotiating with the Biden administration.

It is still unclear to Jerusalem where Washington will stand on the issue under Biden, or under which conditions he would be willing to re-enter the nuclear deal or negotiate a new one.

Once in office, Biden is likely to be preoccupied with the coronavirus in the US and his country's economy and Iran will be something he will have to clear off his desk.

This is both a pro and a con: a con because Biden will be distracted and his administration could potentially agree to conditions it normally wouldn't, just to wrap the issue up; and a pro because it means that the US can push for a better deal.

Yoav Limor

Source: https://www.israelhayom.com/2021/01/03/israel-troubled-by-irans-retribution-dilemma/

Follow Middle East and Terrorism on Twitter

No comments:

Post a Comment