by Mordechai Kedar

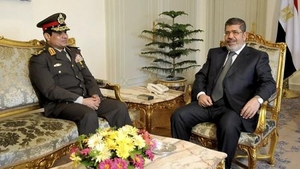

Note: This article was written on Friday, July 5, after Mursi was deposed.

Tahrir Square is filled with rejoicing, because the masses of restless youth have succeeded in removing the "ikhwanji" (denigrating term for "Brotherhood man") Mursi from the president's seat, and it might almost seem as if the problem of political Islam's control of Egypt has been solved. They seem to think that forty million religious Egyptians have disappeared together with their dreams of realizing the fulfillment of their slogan, "al-Islam hu al-hal", "Islam is the solution" to all problems relating to the individual, family, society, state and the entire world.

But reality is more compelling than any decision of the Egyptian Chief of Staff, since he cannot ensure that the Muslim Brotherhood movement will always remain a civil movement without a combative militia. He is well aware that radical and violent organizations have arisen from this movement, such as Al-Gama'a al-Islamiyya, which attacked tourists during the 1990s and whose spiritual leader - Sheikh Amr Abd al-Rahman - tried to topple the World Trade Center in New York in 1993. Or the Egyptian Jihad organization, which assassinated President Sadaat in October 1981, and whose leader - Ayman al-Zawahiri - is deeply involved with the al-Qaeda organization.

The names of organizations such as "al-Takfir wal-Hijra" (Excommunication and Emigration) and "Al-Nagun min al-Nar" (Saved from the Inferno) fill senior officers of the Egyptian army will dread, because they know that there are enough people among the Egyptian population who identify with the radical ideas of these organizations and would set off car bombs and cause mass murder among people that they suspect of helping to remove the Muslim Brotherhood from power, after they had won it legitimately in fair, democratic elections. The crowds of cars and people in Egyptian cities' streets make it impossible to prevent terror attacks, and one small explosion would be enough to create waves of drivers and pedestrians who would run over and kill anyone they came across.

The crowds in the streets of Egypt will increase during the month of Ramadan, which begins on July 9, next week, and religious sensitivities will be heightened as well, which might impel people to deeds and actions that they might not ordinarily do in normal times. The prices of food and clothing, which rise steeply in Ramadan, together with the deterioration in the economic situation, especially among the weak sectors, increase the frustrations of the disillusioned population, and their desire to take revenge on those who brought the present miserable situation upon them increases as well. The radicals see the army and the restless youth as the natural targets, so city squares and military facilities might be the main objectives for terror attacks.

Today, Friday, July 5, will be the first test of the revolution, because the masses that will stream from the mosques into the streets at the end of afternoon prayers might be brainwashed by the Friday sermons in the mosque. The state does not monitor most of the mosques in Egypt, so their preachers can say anything they want to their flock, without fear. Even if today passes peacefully, difficult and important questions are in store for Egypt, primarily whether to allow the Muslim Brotherhood to run in elections for parliament or the presidency. Or perhaps Egypt will return to the way it was in the days of Mubarak, when the Brotherhood was forbidden to appear as a party on the political stage, and here Egypt is confronted with the question "to be or not to be": if it is democratic, how can it prevent the Brotherhood from competing for seats in the parliament or the presidency, and if Egypt does not allow them to run democratically, then it has gone back to being a dictatorship, so what has the rebellion against Mubarak achieved?

===============

Dr. Kedar is available for lectures

Dr. Mordechai Kedar (Mordechai.Kedar@biu.ac.il) is an Israeli scholar of Arabic and Islam, a lecturer at Bar-Ilan University and the director of the Center for the Study of the Middle East and Islam (under formation), Bar Ilan University, Israel. He specializes in Islamic ideology and movements, the political discourse of Arab countries, the Arabic mass media, and the Syrian domestic arena.

Translated from Hebrew by Sally Zahav with permission from the author.

Additional articles by Dr. Kedar

Source: The article is published in the framework of the Center

for the Study of the Middle East and Islam (under formation), Bar Ilan

University, Israel. Also published in Makor Rishon, a Hebrew weekly newspaper.

Copyright - Original materials copyright (c) by the author.