by Burak Bekdil

Erdoğan believed Islam had to take a central role if a historic end to the conflict was to be achieved – one in which the Kurds would surrender their arms and live peacefully with their Turkish Muslim brothers.

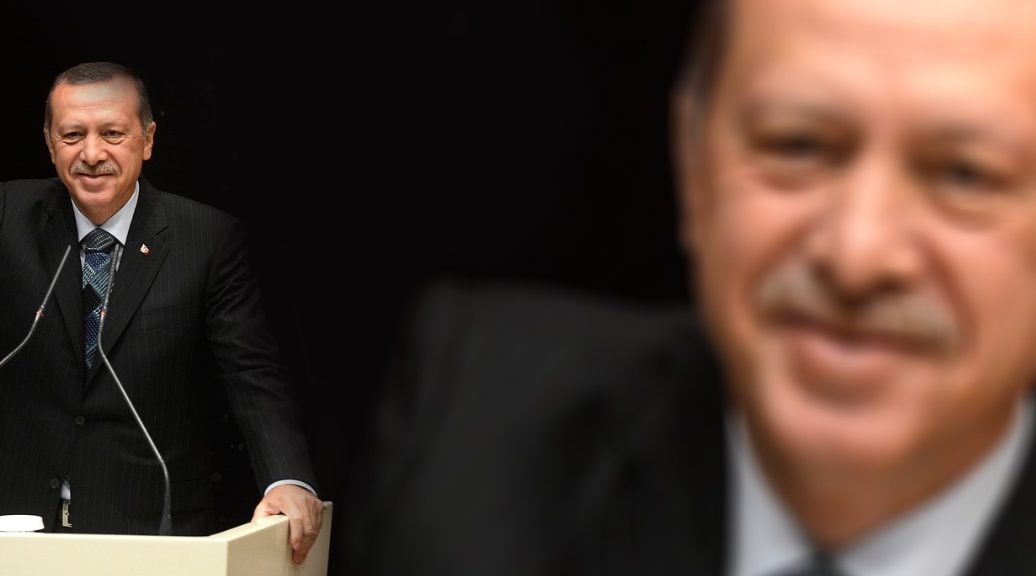

Recep Tayyip Erdogan, image via Pixabay CC

BESA Center Perspectives Paper No. 642, November 15, 2017

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: Turkish

President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan perceives the Kurdish belt along

Turkey’s Syrian and Iraqi borders as the country’s top security threat,

and has recalibrated his policies accordingly. But he has a Kurdish

constituency inside Turkey and will need their votes in 2019. During the

upcoming presidential campaign, Erdoğan will have to find a miracle

equilibrium: how to win Kurdish votes without losing nationalist Turkish

votes?

In 2015, soon after the Turkish people went to the

ballot box, the main Kurdish insurgency group, the Kurdistan Workers’

Party (PKK), ended a ceasefire it had declared two years prior. Just a

few months earlier, there had been hope for peace. Even Turkish

President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s fiercest critics praised him when he

bravely launched a difficult process meant to finally bring peace to a

country that had lost 40,000 people to ethnic strife. His government

negotiated with the Kurds and granted them broader cultural and

political rights, which his predecessors had not. The PKK would finally

say farewell to arms.

Instead, it took up arms once again. Since July

2015, Turkish (and Turkey’s predominantly Kurdish) cities have again

become battlegrounds in an almost century-old Turkish-Kurdish dispute.

Kurdish militants have attacked security forces countless times since

then, while the Turkish military has buried fallen soldiers and raided

Kurdish guerrilla camps in northern Iraq as well as inside Turkey.

Reports of casualties on both sides are a regularity most Turks now

grudgingly ignore.

Erdoğan, an Islamist, had miscalculated again. He

had thought he could solve the dispute through his usual “religious

lens.” He would use Islam as the glue to keep Muslim Turks and Muslim

Kurds united, because after all, why should they fight? They are all

Sunni Muslims.

Erdoğan believed Islam had to take a central role

if a historic end to the conflict was to be achieved – one in which the

Kurds would surrender their arms and live peacefully with their Turkish

Muslim brothers. He wished, accordingly, to restructure Turkey along

multi-ethnic lines, but with a greater role for Islam. But he relied too

much on religion to resolve what is essentially an ethnic conflict. The

experiment resulted in sprays of bombs, suicide attacks, bullets,

rockets, and coffins.

The parliamentary elections that took place on

June 7, 2015 marked a radical shift for Erdoğan from his usual religious

nationalism to ethnic nationalism (both of which have always been part

of his ideological policy calculus, to varying degrees). On that date,

his Justice and Development Party (AKP), after having sought peace with

the Kurds for the previous two years, lost its parliamentary majority

for the first time since it came to power in November 2002. With 41% of

the national vote (compared with 49.8% in the 2011 general elections),

the AKP won eighteen fewer seats than were necessary to form a

single-party government in Turkey’s 550-member parliament. More

importantly, its seat tally fell widely short of the minimum number

needed to rewrite the constitution in such a way as to introduce an

executive presidential system that would give Erdoğan almost

uncontrolled powers.

Amid a fresh wave of Kurdish violence, Erdoğan

gambled on new elections, calculating that the uptick in instability and

insecurity would push frightened voters towards single-party rule. His

gamble paid off. The elections of November 1, 2015 gave the AKP a

comfortable victory and a mandate to rule until 2019. His new ethnic

nationalist and anti-Kurdish policy won hearts and minds among Turkish

nationalists. They then proceeded, two years later, to support

constitutional amendments that paved the way for Erdoğan’s ultimate goal

of one-man rule.

Between June 7 and November 1, 2015, Erdoğan’s AKP

increased its votes by nearly nine percentage points. More than four

points of that rise came from votes from its nationalistic rival, the

Nationalist Movement Party, which shares more or less the same voter

base with the AKP. Even some Kurds, weary of renewed violence, shifted

from a pro-Kurdish party (for which they had voted on June 7) to the AKP

(on November 1).

Since 2015, Erdoğan has been enjoying the fruits

of his newfound ethnic nationalism. He has ordered the security forces

to fight the PKK “till they finish it off,” and has pursued hawkish

politics via the judiciary he controls. Several leading Kurdish MPs are

now in jail on terrorism charges. More than 1,400 academics who signed a

petition “for peace” have been prosecuted and/or dismissed from their

universities. Talking about Kurdish rights is now almost tantamount to

bombing a square in Istanbul.

Across Turkey’s Syrian and Iraqi borders, Erdoğan

has also recalibrated his policy in line with a reprioritizing of

security threats. A Kurdish belt along Turkey’s southern borders is now

perceived as the top threat – worse than ISIS, or Syrian President

Bashar al-Assad’s pro-Shiite (and therefore anti-Sunni, anti-Turkish,

and anti- Erdoğan) regime in Damascus, or the growing Shiite military

presence in northern Iraq (Hashd al-Shaab). In the hope of countering

what he considers the worst of all possible threats, Erdoğan is now a

reluctant partner in the Russia-Iran-dominated Shiite theater in

northern Iraq and Syria.

In Erdoğan’s view, the emergence of a near-state

Kurdish actor in Mesopotamia would be an existential threat to Turkey.

Hence his radical retaliation against the Iraqi Kurdish referendum of

September 25, along with his reluctant alliance with Tehran and

Tehran-controlled Baghdad.

But there is more for Erdoğan to calculate. When

he devises his policy calculus towards the Iraqi and Syrian Kurds, he

must also keep an eye on the Turkish Kurds, whose votes he will need in

2019 when Turks go once again to the ballot box. Election 2019 will be

the most historic race in Erdoğan’s political career – an election he

knows he cannot afford to lose. He needs every single vote, from

Islamists to liberals to nationalists to Kurds. And that makes things

tricky.

Election 2019 will take place at a time when both

Erdoğan and the insurgent Kurds will have less appetite for a new

peace-based political adventure. Kurds trust him less than they did

between 2011 and 2013. At the same time, Erdoğan has discovered that he

wins more votes if he plays to nationalist Turkish constituencies rather

than to Kurdish ones. He will be more reluctant to shake hands with

Kurds than he was in 2013.

Although the Turks have a clear military

advantage, the Kurdish minority possesses a weapon of its own: the

fertility rate in Kurdish-speaking parts of Turkey is higher than in the

Turkish-majority regions. The Kurds may emerge as the Turkish

Islamists’ main rivals in the not-too-distant future simply by virtue of

their having more babies.

There are, moreover, sociopolitical and

demographic reasons to anticipate that both Islamists and Kurds will

perform better in the upcoming Turkish election. From a political

perspective, Turkey is becoming increasingly right-wing and religiously

conservative. F. Michael Wuthrich of the University of Kansas Center for

Global and International Studies has demonstrated that Turkish voting

bloc patterns have progressively shifted to the right, from 59.8% in

1950 to 66.7% in 2011. This pattern, presumably still in progress, will

work in favor of the AKP and any other political party championing

Islamist-nationalist ideas.

But the Kurds’ demographic advantage is

significant. At present, the total fertility rate in eastern and

southeastern, Kurdish-speaking Turkey is 3.41, compared to an average of

2.09 in the non-eastern, Turkish-speaking areas. Erdoğan has urged

every Turkish family to have “at least three, if possible more”

children, but things are not moving as he wishes. The total fertility

rate in Turkey has in fact dropped from 4.33 in 1978 to 2.26 in 2013.

Just as less-educated (and more devout) Turks grew

in number and percentages over the past decades and brought Erdoğan to

power simply by combining demographics and the ballot box, the Kurds may

emerge as the Turkish Islamists’ main rivals by using the same

political weapon.

As he campaigns ahead of the 2019 election,

Erdoğan will have to find a miracle equilibrium: how to win Kurdish

votes without losing nationalist Turkish votes? So far, he has managed

this challenge exceptionally well. He has won nationalist votes, and his

party has come in second in Kurdish regions of Turkey. In 2019,

however, he will face a bigger challenge.

BESA Center Perspectives Papers are published through the generosity of the Greg Rosshandler Family

Source: https://besacenter.org/perspectives-papers/erdogan-turkey-kurds/

Follow Middle East and Terrorism on Twitter

Copyright - Original materials copyright (c) by the authors.

No comments:

Post a Comment