by Caroline Glick

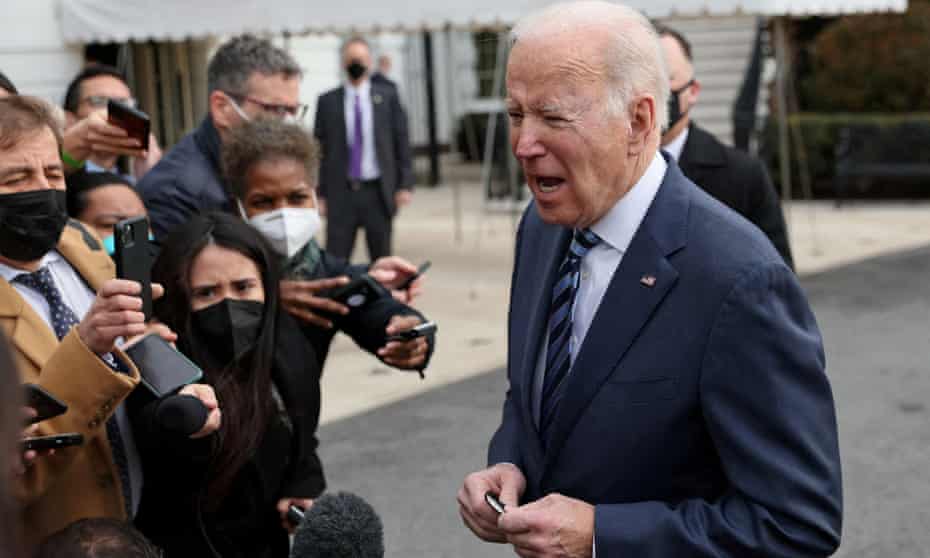

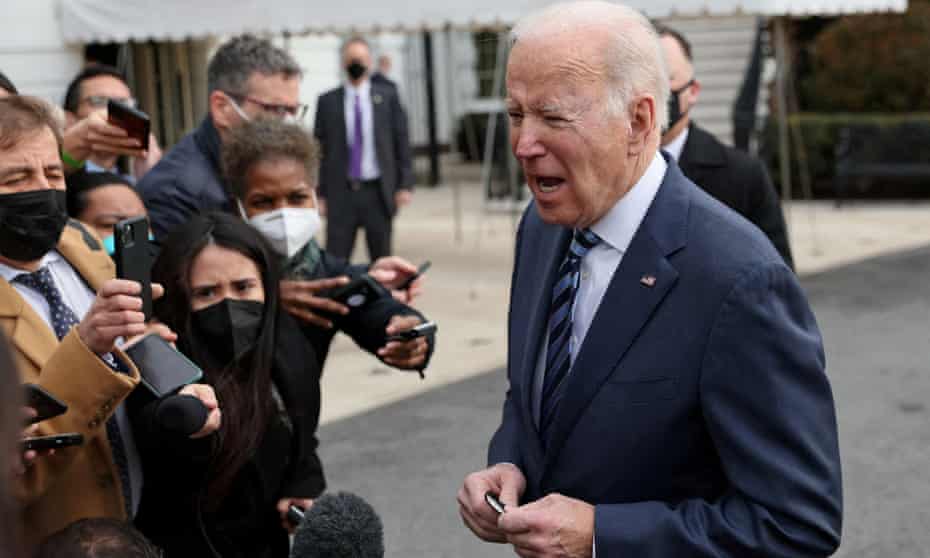

[F]ar from rebuilding U.S. credibility on the world stage after his Afghanistan debacle, Biden’s empty threats of world war have exposed America’s weakness and the hollowness of the U.S.’s commitment to its allies.

Several commentators have argued in recent days that the crisis

between Russia and Ukraine has been a godsend for President Joe Biden

ahead of the midterm elections in November.

The argument is fairly straightforward. With tough talk and without

endangering any U.S. forces, Biden is managing to block Russian

President Vladimir Putin from carrying through on his plan to invade

Ukraine. Since Biden and his advisors have been signaling that such an

event would precipitate a U.S.-Russian war, (i.e., World War III),

simply by talking tough, Biden is preventing a world war. Obviously,

this is an historic, indeed, epic achievement that without question

blots out Biden’s incompetent and strategically disastrous surrender in

Afghanistan from the public’s memory.

While at first glance, this claim seems reasonable, (on Thursday

morning, when these lines are being written, Russia has not invaded

Ukraine), it is problematic on several counts. The first problem with

the claim is that according to an ABC News poll, most Americans don’t

care about the events in Ukraine and believe that the U.S. should stay

out of the conflict. It’s hard to see how Biden’s actions in an area

that Americans are unconcerned with will move the needle of public

support in Biden’s favor. Americans cared about Biden’s decision to lose

the war in Afghanistan and leave in humiliation because it was an

American war which he chose to end dishonorably. Ukraine is not

America’s war. So the public doesn’t care.

Beyond the fact that Americans don’t really care about what happens

to Ukraine, there is a second problem which is that Biden’s messaging on

Ukraine and Russia is demonstrably false and misleading.

The first misleading message that the administration has been using

is that a Russian invasion of Ukraine would precipitate World War III

because it would put the U.S. in a direct shooting war with Russia. This

claim is simply wrong. In his speech Tuesday Biden made clear that the

U.S. will not go to war to defend Ukraine. It will not send U.S. forces

to fight on Ukraine’s behalf. This is a statement that Biden and his

advisors have made multiple times in recent weeks. And the statement on

its own is enough to make clear that there is no chance of a world war

opening as a consequence of a Russian invasion.

Biden’s dismissal of a U.S.-Russian war as a possible outcome of a

Russian invasion is not a function of any anti-war predisposition on his

part. It is a function of four considerations, which are not subject to

change.

First, the U.S. public is unprepared, and unwilling to go to war

against Russia. With 53 percent of Americans opposing U.S. involvement

the Ukraine crisis, a presidential decision to go to war is unthinkable.

Second, the U.S. has no formal commitment to defend Ukraine’s

independence. For nearly twenty years, successive administrations have

worked behind the scenes to block any possibility of Ukrainian

membership in NATO because they don’t want to be formally committed to

protecting Ukraine from Russia.

This then brings us to the third reason the U.S. will not take up

arms to defend Ukraine. While the U.S. national interest is advanced by

an independent Ukraine willing to stand up to Russia, and welcome the

U.S. and the EU as allies, that interest cannot compete with t the U.S.

interest in avoiding war with Russia. And as a result, it is against the

U.S.’s national interest to wage war for Ukraine.

Finally, the U.S. has little military capacity to fight a ground war

in Ukraine against Russia. Russia has 150,000 troops deployed along its

border with Ukraine. Russian President Vladimir Putin can manage their

logistical supply lines because they are in Russia.

The U.S. has neither the forces nor the will to send tens of

thousands of soldiers to Ukraine to fight the Russian army. It cannot

compete.

So far from rebuilding U.S. credibility on the world stage after his

Afghanistan debacle, Biden’s empty threats of world war have exposed

America’s weakness and the hollowness of the U.S.’s commitment to its

allies.

Biden hasn’t only been bluffing about the prospect of world war. He

is also bluffing about sanctions. Biden said Tuesday that if Russia

invades Ukraine, the U.S. will impose sanctions on “key industries” in

Russia. But just as his talk of World War III was entirely empty, so his

threats of sanctions have no foundation in reality.

Immediately after pledging to impose sanctions in retaliation for a

Russian invasion of Ukraine, Biden said that such sanctions – presumably

on Russia’s energy exports to the West — will also hurt Americans in

their pocketbooks.

With inflation rates in the U.S. at 39-year highs, and with public

faith in their president’s stewardship of the economy at all time lows,

you don’t need to be an A-list political consultant to understand there

is zero chance that in an election year Biden will impose sanctions on

Russia that will boomerang against U.S. consumers.

The argument that Biden comes out ahead from the Ukraine crisis also

ignores what Putin has gained from the crisis on the one hand, and what

the U.S. has lost on the other hand.

Without ordering any of his soldiers to cross the Russian border into

Ukraine, Putin has already achieved what he set out to accomplish:

keeping Ukraine permanently out of NATO.

While Biden hasn’t formally agreed not to bring Ukraine into NATO,

his announcement that the U.S. will not defend Ukraine against a Russian

invasion, while 150,000 Russian troops are poised at the Ukraine border

threatening to invade leaves no room for doubt that Ukraine will not be

made a NATO member nation. Not now, and not in the foreseeable future.

To all intents and purposes, Biden’s speech on Tuesday transformed

Ukraine from a U.S. client state into a Russian satellite state.

This brings us to NATO itself. Tuesday Biden claimed that the Ukraine

crisis has made NATO stronger and more unified than ever. But the

opposite is the case. By threatening Kiev, Putin exposed that at least

as far as Russia is concerned, NATO is no longer a functioning military

alliance. Poland, the Baltic states and other former Warsaw Pact nations

that joined NATO after the Cold War continue to view Russia as a

threatening enemy. Germany, France and other Western European NATO

members view Russia as a partner. Throughout the current crisis on

Ukraine, German Chancellor Olaf Scholz has been acting more like

Russia’s ally than America’s. Scholz recently put forward the suggestion

that Ukraine accept the status that Finland suffered throughout the

Cold War. It was independent in its domestic affairs but compelled to

toe Moscow’s line in its security policies and international positions.

Notably, last year Putin penned an article touting precisely this

position.

While it still remains unclear if Putin will invade Ukraine, it is

also unclear why he would feel it necessary to do so. Simply be sending

his troops to the Ukraine border, he ended any chance of Ukraine joining

NATO and his effectively destroyed NATO as an anti-Russian military

alliance.

This brings us to the direct losses the U.S. has suffered due to

Biden’s handling of the Ukraine crisis. Rather than undo the damage he

caused to U.S. credibility with his abject surrender of Afghanistan to

the Taliban, Biden exacerbated the damage. By threatening war one moment

and pledging not to go to war the next, Biden turned himself – and

through him, the United States of America – into a joke on the world

stage. When Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky felt compelled to

tell Biden to tone down his rhetoric about an imminent Russian invasion

twice in under a week, and insist Biden’s warnings did not correspond

with the situation on the ground, it became clear that U.S. support is

not what it once was. Biden’s “support” for Ukraine, has arguably done

Ukraine more harm than good in the present emergency.

When seen in the context of Biden’s wider foreign policy, Biden’s

decision to adopt a saber-rattling posture against while declaring he

has no saber to rattle is even more disturbing. While making entirely

empty threats at Russia, Biden is genuflecting before Iran and China.

Taken together it becomes impossible to claim that Biden’s handling of

the Russian threat to Ukraine has strengthened him either domestically

or internationally.

Given its destructive effect on both the U.S. and NATO, what stands

behind Biden’s strategically indefensible position on Ukraine?

It would seem that like most aspects of Biden’s policies, this one too is rooted in domestic U.S. power politics.

For the past three years, Special Prosecutor John Durham has been

investigating the apparent conspiracy hatched and executed by Hillary

Clinton’s 2016 presidential campaign to defeat first candidate, and

later president Donald Trump by falsely accusing him of being a Russian

agent.

In a court filing last Friday, Durham revealed that the conspiracy

was apparently not limited to Clinton’s campaign apparatus. The Obama

White House, and U.S. intelligence agencies were also involved in the

plot against Trump. Specifically, Durham revealed that both Clinton’s

campaign and partners in the White House unlawfully listened to Trump’s

electronic communications which were carried out at Trump Towers, in his

transition team headquarters, and apparently in the White House, after

he was inaugurated in January 2017.

The false claims against Trump that were generated by the Democrat

Party and the national security establishment and pumped into the

public’s bloodstream by the media made it impossible for Trump and his

advisors to advance their plans to develop constructive relations with

Russia. Their intention had been to entice Putin to abandon Russia’s

partnership with Iran in Syria, and they hoped to divide Russia away

from China as well.

But with Trump and his closest advisors under investigation by a

politicized FBI and Justice Department for allegations of collusion with

Russia generated by opposition research funded by the Clinton campaign,

and with the media pumping the story into the public bloodstream, Trump

could not go through with his planned policies. He was compelled to

oppose Russia at all turns. As a consequence, during his presidency,

Russia grew closer to both Iran and China, to the detriment of the U.S.

In light of the fact that the U.S. has no military option to defend

Ukraine, and that sanctions on Russia will harm the U.S. economy, the

smart move in Ukraine would have been to cut a deal with Putin that

conceded Ukraine in exchange for Russia cooperation on other fronts

important to the U.S. Had Biden sought such a deal, he would have

preserved NATO intact, caused no further harm to U.S. credibility and

perhaps, gotten Russia on board in areas where Russia and the U.S. have

common interests. But after five years during which Biden and his party

have painted Putin as humanity’s Enemy Number 1, Biden had no choice but

to continue castigating Putin and Russia. And so he did. And thus NATO,

and the U.S.’s credibility as an ally have become the latest victims of

the Trump-Russia conspiracy.

Originally published in Israel Hayom.

Caroline Glick

Source: https://carolineglick.com/bidens-victory-against-putin/

Follow Middle East and Terrorism on Twitter