by Assaf Orion

China-Iran relations are the junction between an important economic partner of Israel and the most serious external threat to its national security. The strategic agreement between Beijing and Tehran signed recently continues their deep years-long relations, and reflects a low point in China-US relations. Beijing’s assistance to Iran to emerge from its isolation and rebuild its economy runs counter to Israel’s interests, while the military-technological and intelligence cooperation between them heightens the military threat to Israel and others in the Middle East and the Indo-Pacific. This trend demands adjustments in Israel’s policy, with an emphasis on more rigorous risk management and an updated dialogue with strategic partners

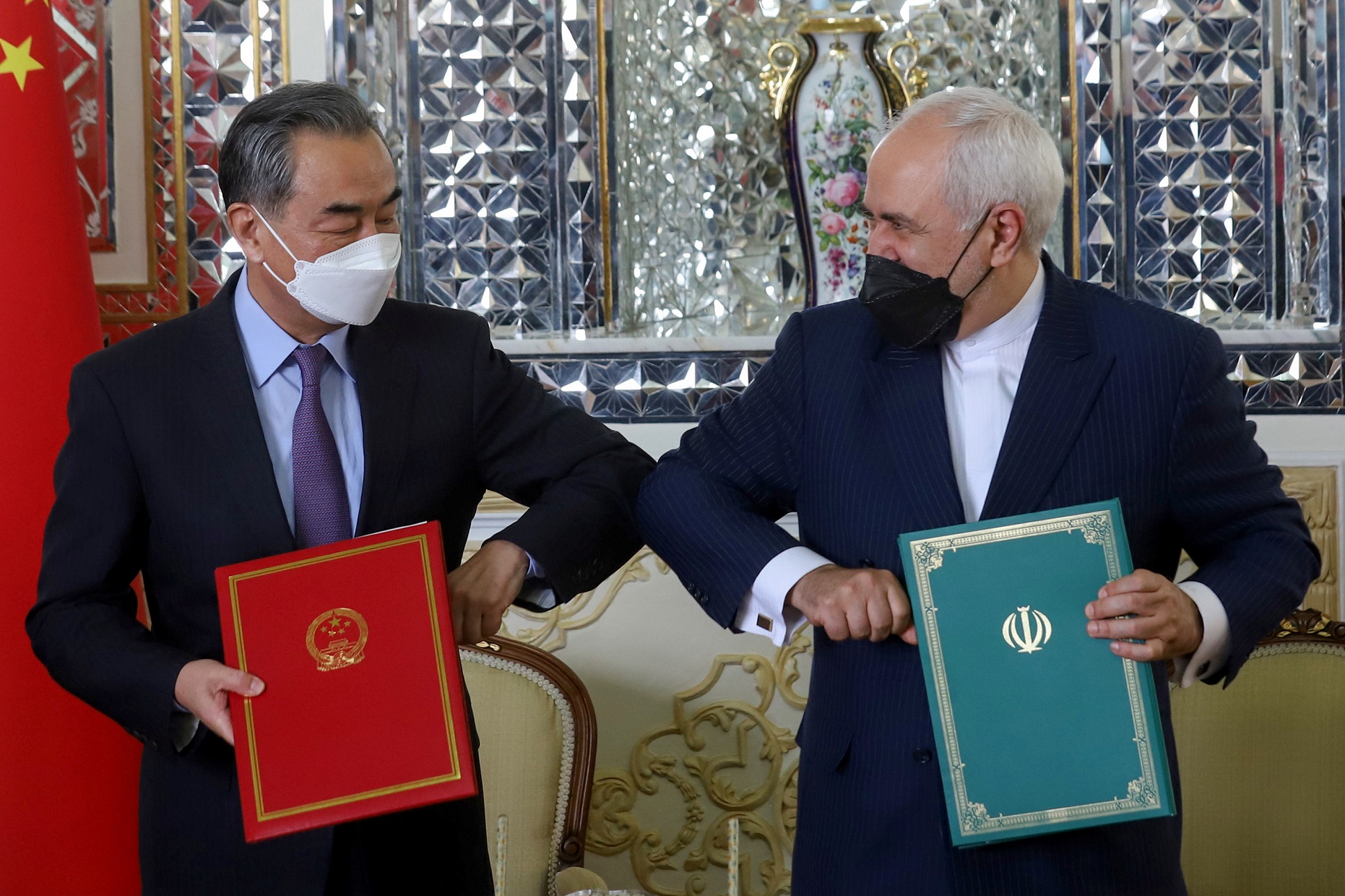

On

March 27, 2021, during a visit to Tehran by China’s foreign minister,

China and Iran signed a strategic agreement focusing on large-scale

investments by China in Iran in exchange for a supply of oil over the

next 25 years.[1]

The wording and details of the agreement have not yet been made public,

but its very achievement helps ease Tehran’s economic isolation,

imposed by the United States. To the extent that the signed agreement

corresponds to the draft document leaked by Iran in July 2020, it

includes agreement on progress in military, technological, and

intelligence cooperation that is fraught with potential risks to

Israel's security. Following the publication of the draft, the Trump

administration stressed its demands of Israel to cool its relations with

China and limit Chinese penetration of Israel's economy. US Special

Representative for Iran Brian Hook reportedly said at the time, "China

[cannot] have it both ways. They can’t strengthen Iran, which chants

'Death to Israel,' and have a business-as-usual relationship with

Israel…I am sure Israel will do the right thing on China."[2]

Concurrently, it was reported that in view of the growing competition

by Chinese companies in the infrastructure sector in Israel at the

expense of local companies, the Israel Builders Association demanded

that government company NTA Metropolitan Mass Transit System invalidate

the tender won by PCCC, a Chinese company, for construction of a bridge

in Tel Aviv. The Builders Association asserted that PCCC's cooperation

with Iran jeopardizes Israel's security and constitutes a breach of the

law banning contact between an Israeli government corporation and a

corporation maintaining business relations with Iran.[3]

Not

surprisingly, however, the situation is more complicated than the

messages and narratives that portray stark simplicity in the service of

various interests. The overall picture is one of complexity and

tensions, both in Iran-China relations and between different goals in

their respective policies. The relations are thus a far cry from an “all

weather” solid alliance guaranteeing the Islamic Republic of Iran full

strategic support from the People's Republic of China. Yet the

developing bilateral relations harbor negative trends for Israel's

national security, heighten tensions in Israel's own policy, and require

policy adjustments, more rigorous risk management in Israel's relations

with China, and greater strategic cooperation with the United States

and the Gulf countries.

Converging and Diverging Interests

China and Iran share a wide interest base: both seek to weaken the United States, decrease its role in the international order, and undermine its alliances. They both oppose external intervention in their affairs, and fear efforts seeking changes to their authoritarian regimes. The two countries suffered from the Trump administration's policy, and are looking forward to relief under the Biden administration. For Iran, China constitutes an important major power counterweight to the United States and an Eastern alternative to the West’s economy, especially under sanctions. For China, Iran is a useful energy supplier and a market of considerable size, and it occupies a central location on the road to Europe for the Belt and Road Initiative. No less importantly, Iran poses a strategic challenge to the United States in the Middle East – somewhat similar to the challenge posed to it by North Korea in East Asia.

At the same time, the two countries' interests do not overlap entirely, and there are quite a few tensions between elements of their policies. China, whose core interests are in East Asia, wants to drive the United States out of this immediate neighborhood; it benefits from America having been sucked into the Middle East and subsequently pinned down there, and its ensuing struggle to gravitate to the Indo-Pacific. For its part, Iran seeks an "imperialism and Zionism-free Middle East," i.e., with United States forces gone and with Israel destroyed. China, however, benefits from Israel's innovation, invests in Israel's economy, and certainly does not want its destruction. As an oil importer, China wants low energy prices, while Iran, as an exporter, prefers them high. China prefers stability in the Middle East that allows a safe environment for economic activity, while Iran is a systemic destabilizer across the region, igniting conflicts and fomenting unrest. Energy and navigation security are important interests for China, but in recent years Iran and its proxies have repeatedly attacked energy infrastructure, oil tankers, and other vessels in the Arabian peninsula, the Persian Gulf, the Arabian Sea, and the Red Sea. In the internal sphere, given the Muslim minorities in its population, China is somewhat perturbed about Sunni radicalism and terrorism and their infiltration to its territory, while Iran is maneuvering between fighting against ISIS and harboring al-Qaeda. These tensions reflect China's interest in principle in moderating Iran's regional aggression – a principle with positive potential should Beijing choose to exert its influence to that effect.

There are also internal tensions between elements in each country’s policy. While China wants to weaken the United States, it also relies on it as a security provider in the Middle East. China wants to protect its growing interests in the region, while at the same time it is concerned over entanglement there, and seeks to avoid the costs of inflexible commitments and direct involvement. On the other hand, while economic ties with China are essential for Iran, there is opposition in Iran to dependence on outside powers in general, and fear of excessive Chinese influence in particular, combined with dissatisfaction about the Iranian market being flooded with Chinese goods, at the expense of local producers and merchants.

RAND Corporation researchers Andrew Scobell and Alireza Nader described China in the Middle East as "an economic heavyweight, a diplomatic lightweight, and a military featherweight."[4] Recent studies conducted at the Institute for National Security Studies (INSS) in each of these areas highlight important insights for Israeli policy in the context of Chinese-Iranian relations.

In the economic sphere, China has contributed heavily to the Iranian economy, and particularly during the period of sanctions, thereby helping Iran to withstand the pressure of the sanctions and indirectly also increasing the resources available to Tehran for its destabilizing activities across the region. That said, China's economic relations with Tehran are smaller in scope than with Saudi Arabia and United Arab Emirates. Moreover, economic relations with Iran have shrunk over the past five years, in part to reduce China's exposure to sanctions, while relations with the Gulf states and Iraq expanded significantly. In addition, in part because of China's capital outflow control measures, the volume of China's trade with Iran and investments there declined. Simultaneously, Iranian dependence on China as a trade partner greatly increased, primarily as an importer of Iranian oil (as of 2019, China accounts for about a third of Iran's trade and half of its oil exports). At the same time, Iran's share of the energy supplied to China and in Chinese trade has sharply decreased as a result of a clear Chinese effort to diversify its sources and partners, but the sanctions have prevented Iran from such diversification. This trend reveals another source of tension between Iran's goal to have the sanctions against it lifted and to diversify its economic partners, and China, deriving major economic advantages from Iranian isolation under sanctions and minimal competition. Furthermore, as shown by China's relations with other countries, mostly in its nearer environment (Australia, Japan, South Korea, North Korea, and of course Taiwan), Beijing regularly leverages other countries' economic dependence for promoting its political goals. Iran's clear economic dependence on China, therefore, constitutes potential leverage for China to influence Iran, should it choose it use it.

In the political sphere, China and Iran signed a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership (CSP) agreement in 2016. This term describes China's relations with over 30 countries, among them Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Algeria, and United Arab Emirates. Parallel strategic partnerships with countries hostile to one another are a signature of China’s policy in the Middle East, as Beijing as a rule refrains from taking sides and involvement in conflicts, focusing instead on the promotion of its interests, mainly in the economic sphere. Israel and China signed an Innovative Comprehensive Partnership agreement in 2017. This singular title emphasizes the two countries’ sphere of shared interests, while avoiding a description of their relations as "strategic"; this is a definition that is mutually comfortable. China carefully maintains its advantageous position vis-à-vis Iran in the political sphere as well, with Iran having waited five years to sign the strategic agreement with China on the one hand, while still waiting for acceptance as a full member of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) on the other.

No less complex is China's policy on the Iranian nuclear project. China provided technological and material assistance for the Iranian nuclear program until 1997, when it halted this aid in the framework of understandings with the United States on Taiwan. China thereby reduced its support of Iran in the service of two of its vital interests: its strategic relations with the United States and prevention of independence by Taiwan, which it regards as an integral part of one China and its sovereign right. Although it has since been reported that Chinese companies’ supplies aided Iran in its nuclear and missile development, the Chinese regime's part in these activities is unclear. Like Russia, China supported the UN Security Council resolutions on Iran's nuclear program, including those imposing sanctions on Iran, but at the same time diluted the resolutions and prevented their having “teeth” for viable enforcement. China also took part in formulating the 2015 nuclear agreement (JCPOA), and eventually signed it alongside the other major powers. Promoting this agreement postponed the risk of a military crisis, prevented a legitimate basis for external intervention in Iran (an important principle in Chinese foreign policy), and at the same time gave China an economic advantage in trade with Iran, under the shadow of the sanctions. As evident by the Biden administration's outreach to China in the framework of its efforts to renew negotiations on the Iranian nuclear program, China continues to be an important player in the talks with Iran, and its support is important for the success of these United States efforts. For Israel, it is important to realize that China is more concerned about military crises and external regime change attempts than about nuclear weapons in the hands of rogue countries like Iran and North Korea.

In the military-security sphere, there are growing indications of a trend, alarming for Israel, of increased military, technological, intelligence, and security cooperation between China and Iran. The transfer of Chinese military technology, which Iran is using to develop and produce weapon systems, some of which have already inflicted damage on Israel, is not a new threat: Chinese-manufactured cluster rockets were fired against Israel during the 2006 Second Lebanon War, and the Hezbollah missile that hit the Israeli naval vessel Hanit then was a variant of the Chinese C-802. Beyond this, however, since Chinese President Xi Jinping’s rise to power, there have been mounting public signs of increasingly close military cooperation between China and Iran: military exercises, port visits, and visits by senior naval, military, and defense figures. One salient area of these developing military relations is naval warfare, with a special emphasis on anti-ship missiles that threaten Israel in the Mediterranean Sea and the Red Sea, as well as the Gulf states and the United States navies in the Middle East and the Western Pacific. The strategic agreement between China and Iran, to the extent that the draft reflects the final version, outlines a zone of agreement on cooperation in intelligence, cyberwarfare, precision navigation systems, weapons research and development, and military training and instruction. As in other areas, the implications of the agreement will depend on its actual details and how they are implemented.[5]

Significance for Israel

The principal, prominent, and familiar tension in Israel's relations with China stems from the Israel-China-United States triangle, i.e., between China as an important economic partner of Israel and the United States as Israel's irreplaceable strategic ally. To the United States, China is its main rival in the great power competition and a grave threat to America's national security and global status. Israel and other United States partners are therefore required to restrict aspects of their relations with China and tighten their management of the risks incurred in those relations, including in economic spheres, and with a special emphasis on technology.

Chinese-Iranian relations add a complex challenge to Israel's policy by virtue of being the junction between a global power that is an important economic partner of Israel and a regional power that constitutes the principal and most serious external threat to it. China's relations with Iran are the convergence point of the number one threat to the United States and the number one threat to Israel. This suggests a significant area for extensive cooperation between Israel and the United States.

China’s Leverage on Iran: Will It Use It?

China

is Iran’s economic and strategic prop, and serves as a counterweight to

United States pressure and a means of evading the sanctions regime.

Iran's dependence on China has increased greatly in recent years, and

China's potential influence on Iran has grown accordingly. China also

has an interest in principle in stabilizing the environment and reducing

risks to its interests in the region, and thus in moderating Iran's

aggression. The question therefore arises whether China will now be

inclined to influence Iran to reduce the threats to its surrounding,

including Israel.

Israel has conducted a prolonged and sensitive dialogue with Russia about the supply of arms to Israel's enemies, with partial success – despite the personal relationship between the two countries' leaders, the proximity of their militaries (since Russian forces deployed to Syria), and their deep mutual familiarity, thanks to the large portion of the Israeli public with roots in the Soviet Union. In contrast, Jerusalem's access to the leadership in Beijing is extremely limited, and Israel's relations with China are much narrower than with Russia. Consequently, Israel has little ability to influence China’s policy to moderate Iranian aggression and reduce Chinese aid for the development of Iran’s military threats. Nevertheless, Israel should voice its concerns to China about Iran's threats, both nuclear and conventional, and about China's contribution to the aggravation of these threats.

At the great power level, coordination with China is important for the United States in its effort to reach agreements with Iran and on other global issues, such as climate change and the COVID-19 pandemic. In the 1990s, China demonstrated its willingness to halt its nuclear assistance to Iran, putting its core interests in Taiwan and its relations with the United States first. Israel's influence on Chinese policy in the region therefore depends to a large extent on its success in integrating its goals with those of Washington, the main player in this context. Israel must also keep in mind the gaps between its positions and those of each of the major powers, and the extent and intensity of their other interests, while realizing that it may be called on to provide a quid pro quo in other areas for this assistance.

Regionally, Iran is not China's most important partner in the Middle East. Data on China's economic and energy relations show that the Gulf states are more important, especially Saudi Arabia and United Arab Emirates. The visits by Chinese leaders to the region also serve a broad and general perception of the web of Chinese interests there. President Xi Jinping visited Iran, Egypt, and Saudi Arabia in early 2016, while the stopping places on his foreign minister's visit in late March 2021 were Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Iran, United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, and Oman.[6] Following the signing of the Abraham Accords, which highlighted the shared interests between Israel and the Gulf states and their perception of Iran as a common threat, Israel should coordinate its policy on the matter with them too, and with them strive to exert a positive influence the policies of both Washington and Beijing, even though prospects for success in this endeavor are rather modest.

Iran Jeopardizes China's Interests: Will China Moderate Iran?

Beyond China's policy on the nuclear issue, important lessons for Israel emerge from Beijing’s reaction to the attacks initiated by Iran in the Gulf during 2019 against both oil tankers and oil infrastructure in Saudi Arabia. In these events, China confined itself to calling on all parties to exercise restraint, and refrained from putting public pressure on Iran. The same approach seems to reflect China’s stance following the reported maritime attack exchange between Israel and Iran. Nevertheless, in April 2020 it was reported that the Iranian Revolutionary Guards had seized a tanker in the Persian Gulf, but quickly released it when it turned out to be Chinese.[7] Presumably, China reached tacit understandings with Iran that its ships would not be harmed, but these understandings did not extend to tankers of other countries, or to the energy infrastructure of the Gulf countries with which China also signed Comprehensive Strategic Partnership agreements. It is therefore likely that as an expression of its policy of avoiding taking sides in regional conflicts, China will make no real effort to restrain Iran when it attacks Israel directly or uses Hezbollah and its other proxies. Consequently, despite the risk to China's economic interests in Israel, it can be expected to confine itself to public calls for restraint on both sides. It should therefore not be expected that operation of the Haifa Bay shipping containers pier by Chinese company SIPG in 2021 will deter Hezbollah and Iran from attacking Haifa Port or the city of Haifa, should they decide to do so. On the other hand, Israel should take into account that China opposes Israel's military action against the Iranian nuclear program, and may try to deter such action using the range of tools available to it.

Assaf Orion

Source: https://www.inss.org.il/publication/iran-china-cooporation/

No comments:

Post a Comment