by Hugh Fitzgerald

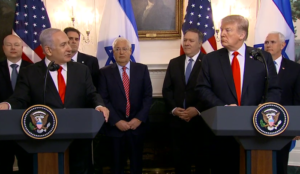

The United States, in one of its most important decisions concerning Israel and the Arabs, on March 21 recognized the Golan as an integral part of Israel. The case for that recognition is very strong.

In June 1967, Israel was forced to fight a three-front war of self-defense against Egypt, Syria, and Jordan. It managed to defeat all three of its enemies within six days. In its victory, it took the Sinai from Egypt, the West Bank from Jordan, and the Golan Heights from Syria. It is the Golan that has just been in the news, for the American government has at long last recognized the Golan as part of Israel.

The Golan Heights are particularly important for Israel’s security. They loom over Israel on one side and Syria on the other. At its highest point, on Mount Hermon, the Golan is more than 9,000 feet high. The country that controls the Golan has a huge advantage over its enemy below. For nearly twenty years, that country was Syria. From 1948 to 1967, the Syrians had used the Golan for one main purpose: to shell the Israeli farmers far below. Though there are different views in Israel on the disposition of the West Bank, there was no disagreement when Israel formally annexed the Golan in 1981.

Since 1981 no other countries have recognized the legitimacy of Israel’s annexation of the Golan, until just now. The United States, in one of its most important decisions concerning Israel and the Arabs, on March 21 recognized the Golan as an integral part of Israel. The case for that recognition is very strong.

First, the Golan was won by Israel in a war of self-defense against three Arab aggressors. The 1967 war effectively began when Egypt’s President Gamal Abdel Nasser, who declared a blockade to prevent Israeli ships from using the Straits of Tiran, moved tens of thousands of Egyptian troops deep into the Sinai, while demanding, and getting, the removal of U.N. peacekeepers so that his army, as he promised to hysterical Cairene crowds, could march north unhindered and destroy the Jewish state. Meanwhile, Syrian troops and artillery on the heavily-fortified Golan prepared for attack, but Israel attacked first and pushed the Syrians off the Golan and and back into Syria. Given the Golan’s enormous military value, in 1981, Israel formally annexed that plateau that loomed over the Galilee.

It has long been a principle of public international law that when an aggressor state loses in a war, the victor has a right to keep territory won in that war. For if it were not the case, if any aggressor who lost a war could be assured of having territory he lost returned to him, there would be little incentive for a would-be aggressor not to engage in war. The map of the world has been drawn and re-drawn by wars. Think of how much territory the Germans permanently lost after World War II, fully 25% of the territory of prewar Weimar Germany, to Poland (East Prussia) and the Soviet Union (among other territories it won, Russia holds onto Kaliningrad, the former Königsberg, which is totally surrounded by Poland and Lithuania). Or take the example provided by the United States. By the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, in 1848, which ended the Mexican-American War, the U.S. gained the land that makes up all or parts of present-day Arizona, California, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming. By its victory in the Spanish-American War, the United States won Guam, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines as territories.

Another example is Alto Adige, which under Austrian rule had been known as the Sudtirol, which was awarded after World War Ito Italy, one of the victorious Allies, by the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye. No one then, save for the Austrians themselves, found the Italian takeover of the Alto Adige as objectionable, and now everyone concedes that it is an integral part of Italy.

That was the accepted rule in international law. But things changed when it came to dealing with the consequences of Israel’s spectacular victory in the Six-Day War. Until then, the so-called “international community” had raised no objections to the acquisition of territory by those who were victorious in a war of self-defense. With Israel, things would be different.

After the Six-Day War, there was much debate and wrangling at the U.N. as to how to treat the territories Israel had won. Resolution 242 was the result. The Resolution contains a clause emphasizing “the inadmissibility of the acquisition of territory by war.” This clause has been endlessly trotted out by the Arab side, but it conflicts with two other, even more important parts of Resolution 242. The first is the call for the “Withdrawal of Israel armed forces from territories occupied in the recent conflict.” The phrase “from territories” was fought over; the Arabs wanted the main drafter of the document, the British U.N. Ambassador Lord Caradon, to put in the words “all the” or “the,” so that the phrase would now call for “withdrawal from all the territories” or “withdrawal from the territories.” This Lord Caradon most explicitly refused to do; he said that he knew that that would be tantamount to pushing Israel back into the unacceptable 1949 Armistice Lines.

Here are Lord Caradon’s later discussions of the meaning of 242:

The chief drafter of 242 was Britain’s permanent representative to the UN, Lord Caradon (Hugh Mackintosh Foot). In a February 1973 interview with Israel Radio, he noted that “the essential phrase which is not sufficiently recognized is that withdrawal should take place to secure and recognized boundaries, and these words were very carefully chosen: They have to be secure and they have to be recognized. They will not be secure unless they are recognized.To summarize:

And that is why one has to work for agreement. This is essential.

I would defend absolutely what we did. It was not for us to lay down exactly where the border should be. I know the 1967 border very well. It is not a satisfactory border. It is where troops had to stop in 1949, just where they happened to be that night. That is not a permanent boundary.”

On June 12, 1974, Lord Caradon told Beirut’s Daily Star that “it would have been wrong to demand that Israel return to its positions of 4 June 1967 because those positions were undesirable and artificial. After all, they were just the places the soldiers of each side happened to be the day the fighting stopped in 1949.

They were just armistice lines. That’s why we didn’t demand that the Israelis return to them and I think we were right not to.

In a 1976 interview published by the Journal of Palestine Studies, Lord Caradon was asked why his resolution mentions withdrawal from “occupied territories” rather than from “the occupied territories.” He responded: “We could have said: well, you go back to the 1967 line. But I know the 1967 line, and it’s a rotten line. You couldn’t have a worse line for a permanent international boundary. It’s where the troops happened to be on a certain night in 1949. It’s got no relation to the needs of the situation.

The demand for an Israeli retreat to “secure and recognized boundaries,” Lord Caradon stressed, was not meaningless verbiage: “We deliberately did not say that the old line [the June 4, 1967, line, i.e., the 1949 armistice line], where the troops happened to be on that particular night many years ago, was an ideal demarcation line.”

Lord Caradon reiterated the essence of the 242 logic on The Mac- Neil/Lehrer Report, on March 30, 1978: “We didn’t say there should be a withdrawal to the ‘67 line; we did not put the ‘the’ in, we did not say ‘all the territories’ deliberately. We all knew that the boundaries of ‘67 were not drawn as permanent frontiers; they were a cease-fire line of a couple of decades earlier… We did not say that the ‘67 lines must be forever.

According to the traditional laws of war and peace, Israel has at least as good a claim to the Golan Heights as Russia does to Kaliningrad (which it took from Nazi Germany in World War II), or perhaps even better, because while Kaliningrad could not possibly again become a place from which Germany might attack Russia, with which the city does not even share a border, if the Golan were returned to Syria, it would inevitably again become a place from which the Syrians would resume their shelling. Israel has at least as good a claim to the Golan as the United States did in 1848 to all or parts of present-day Arizona, California, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming, which it won in the Mexican-American War. Israel has at least as good a claim to the Golan, a place from which attacks had repeatedly been launched by the Syrians, as Italy does to the Alto Adige, which it won during the First World War, and from which no Austrian attacks had come.

Lord Caradon stressed that Israel was not obligated by Resolution 242 to return to the pre-1967 armistice lines, and had a right to live in “secure and recognized boundaries.” “Secure” boundaries means “defensible” borders, and military control of the Golan Heights, any fair-minded visitor would conclude, is essential to Israel’s defense.

Hugh Fitzgerald

Source: https://www.jihadwatch.org/2019/03/hugh-fitzgerald-washington-recognizes-the-golan-as-part-of-israel-part-one

Follow Middle East and Terrorism on Twitter

No comments:

Post a Comment