by Yoav Limor

For the last six months, the IDF has been working feverishly to prepare for a possible attack on Iran's nuclear facilities. It entails incredibly complex strategic and diplomatic planning, along with preparations for possible responses from Iran, Hezbollah, and Gaza.

A lot of words have been devoted in the past few weeks to the possibility of an Israeli attack on Iran. One after another, senior officials in the defense establishment and the political echelon have made it clear that as far as Israel is concerned, "all the options are on the table" when it comes to stopping Iran from developing nuclear weapons.

There is a clear purpose to these threats: to push Western powers to take a more aggressive line on Tehran. They are mostly aimed at the US administration, which has consistently declared that it will not allow Iran to nuclearize, but in effect, is taking a passive stance. To put it simply, Israel is telling the world that if it won't stop Iran, we will have to take military action.

Israel made a similar threat a decade ago, one that was backed up by practical plans for an attack: Israel wanted the world to see that its air force was drilling long-range flights and strikes, and wanted it to know that it was discussing the optimal timing for an attack. US intelligence – and that of other countries, obviously – did not miss the IDF's announcements of high alert ahead of a possible imminent attacks.

All this did the job. The world was pressured by the possibility of an Israeli strike, and took action. The US launched secret talks with Iran, which led to the signing of the JCPOA in 2015. Iran stopped enriching uranium and got rid of the stocks of enriched uranium it already had. The possibility of an Israeli attack was taken off the table, followed by accusations back and forth between the political leadership (Benjamin Netanyahu and Ehud Barak) and the military leadership (Gabi Ashkenazi and Meir Dagan) at the time about what the correct course of action had been, and who torpedoed whom.

While the Iran nuclear deal was in effect, Israel fell into a certain complacency. Assuming that as long as the deal was valid, there would be no military action against Iran's nuclear program, the plans for a strike were shelved, and never underwent the necessary updates and adjustments needed to keep them relevant in light of the changes of the past 10 years.

Even after the US withdrew from the nuclear deal in 2018, Israel was still asleep at the wheel. The assumption was that one of three scenarios would play out: The Tehran regime would collapse under the crippling sanctions the US applied after it pulled out of the deal; the Iranians would beg to sign a new deal, and it would be possible to make it a better, stronger, longer-term one; or Donald Trump would be reelected and order an American strike on Iran's nuclear facilities.

None of these came to pass. The Iranians proved impressively determined, and today – despite a terrible economic situation that includes 30 million people living below the poverty line, crumbling infrastructure, and the Iranian rial at an unprecedented low – they aren't blinking when it comes to their nuclear program.

This hardline policy is being led by a brutal regime that has not been destabilized, and apparently won't while US President Joe Biden is in office (and most likely wouldn't have happened even if Trump had been reelected).

The American withdrawal from the deal prompted the Iranians to hit the gas on their nuclear development. It didn't happen immediately, but in the past few years they have made impressive progress, not hesitating to skip over their commitments under the deal, especially in everything having to do with a ban on installing advanced centrifuges and enriching uranium to a high rate, in large quantities. Recently, they also started enrichment at an underground facility at Fordo, which is much better-defended against a possible attack.

Israel is following this all closely, but took too long to respond. For example, to attack Iran, it will be necessary to refuel mid-air. Currently, the IDF depends on 50-year-old aircraft that need to be replaced immediately. At the end of 2018, then-Defense Minister and IDF Chief Avigdor Lieberman and Gadi Eizenkot approved a broad equipment acquisition plan that included the purchase of new fueling aircraft. But the new IDF Chief of Staff, Lt. Gen. Aviv Kochavi, wanted to delay the decision so it would fall in line with his multi-year plan. Then Israel found itself in a political maelstrom of repeated elections and no state budget. The result: a two-year delay to the decision (which was finally approved at the end of 2020 and inked in early 2021) and therefore to the acquisition of the equipment.

The IDF was waiting for a budget from outside (a "box," as it is termed in the military) to start preparing again for the possibility of an attack on Iran. Kochavi preferred to channel funds to other things, like the multidisciplinary Tnufa unit he set up as part of his multi-year plan. When other high-ranking IDF officers, primarily Israeli Air Force commander Maj. Gen. Amikam Norkin disputed his decision, Kochavi responded that that IDF would be given a "box" like it had previously to deal with the Iranian issue and other matters, like air defense and the construction of security barriers.

When Biden was elected US president, the option of an American attack on Iran was dropped, and then the penny dropped for Israel. At the start of this year, Kochavi revived the military option in an aggressive speech at the Institute for National Security Studies. Once the new government was forced, he got the "box" he had been hoping for – special funding of over 5 billion shekels ($1.6 billion) for three years for preparations to attack Iran.

As a result, for the past six months the IDF has been working feverishly to make the military option a relevant tool. The Israeli military currently has plans and capabilities, but the attention and resources allow it to improve them with every month that passes. This, incidentally, is why many senior Israeli officials support a return to the previous bad deal; it might not keep Iran from developing nuclear weapons, but it will keep it farther away from them, and will allow Israel time, after which – in another three to five years – it should have an effective battle plan against Iran, of which attacks on Iran's nuclear facilities are only one element.

Still, Israel could find itself having to decide on a strike before that, for a number of reasons: the nuclear talks could collapse, leading to Iran continuing its nuclear program until it reaches the nuclear threshold; a temporary deal that Iran will constantly challenge; or a return to the original nuclear deal, which Iran would secretly violate. And there could be other reasons that have nothing to do with its nuclear program, like an Iranian attack on Israel using cruise missiles fired from Yemen or Iraq in response to some Israeli action or other. An attack of this type, especially if it results in wounded, could lead to an Israeli strike on Iranian turf.

According to Sima Shine, former head of the Mossad's research division and now a senior researcher at the INSS, "No Israeli prime minister will allow Iran to become a nuclear power on his watch. The question we need to ask ourselves is what we want to achieve by an attack, and how capable we are of doing it."

This question is not part of the public discourse in Israel, which is limited to whether there will or will not be an attack. For the Israeli public, an attack means that planes will suddenly appear in the Iranian sky, drop bombs that will send Iran's nuclear facilities up in flame, after which our heroic pilots will return home and be greeted with cries of joy, which is what happened after the strikes on the Iraqi nuclear reactor in 1981 and the Syrian nuclear reactor in 2007.

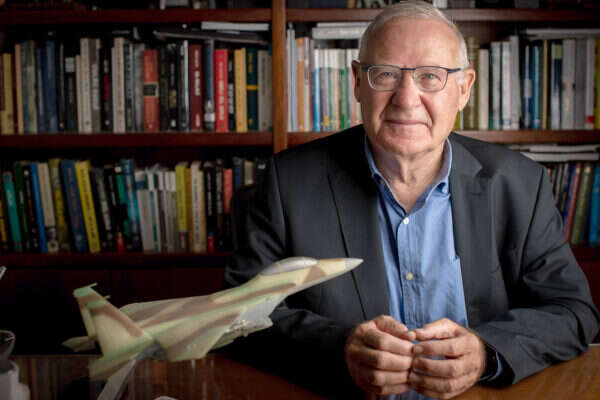

"The Iranian project is farther away, better defended, and more compartmentalized than the projects attacked in the past," says Maj. Gen. (res.) Amos Yadlin.

"In Iraq and Syria, we had the advantage of surprise, and here, we don't. Israel has already proven that it can find creative ways of overcoming these obstacles, but it's a much more complicated event," Yadlin says.

The dramatic change is not only in comparison to the destruction of the Iraqi and Syrian reactors, but also to the situation that existed in 2010, when the option of an attack was first raised. Then, the Americans controlled Iraq and there was a need to coordinate with them, and Iran's nuclear program was much newer and less protected. Since then, Iran has started using the Fordo facility, scattered sites related to its nuclear program throughout the country, and tripled its air defenses, adding dozens of batteries – including Russian S-300 systems as well as systems the Iranian military developed based on Russian and Chinese systems. Iran's air defenses are much more advanced than those of Syria, which the IAF is able to handle in the strikes it carried out there.

The planning stage for an airstrike on Iran is longer than you might think. A senior IDF official told me this week that "There won't be a situation in which someone makes a decision and 24 hours later there are planes in Tehran. We'll need a long time to get the system ready for war, because our working assumption needs to be that this won't be a strike, but a war."

This definition, war, is part of how the IDF's thinking has evolved in the past few months. It is no longer looking at a localized strike on nuclear facilities, but preparing for war. This will be a different war from any we have known – no 7th Division or Golani or shared borders, but multiple different fronts in which battles are waged in multiple ways. One need only watch the maritime battles being waged between Israel and Iran in recent months to understand the potential, which extends far behind Iran's borders to the missile and rocket systems its satellites maintain in Yemen, Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, and the Gaza Strip.

Attacks like these require models – mock training on identical targets at similar distances, to get the system used to what is expected of it on the way to Iran and back. In the past, the IDF would train relatively easily; the enemy was always behind technologically and unable to detect the preparations. Anyone who did, like the Americans – in the case of the strike on Syria's reactor – would have been in on the secret anyway.

Today, the world is equipped with sensors everywhere that will not allow a large contingent of aircraft to take off without alerting the enemy. To obscure the preparation, the IAF will need to create an ongoing routine of drills, which comes at an immense expense – money, fuel, replacement parts, flight hours, and reservist days.

At the same time, Israel will have to make sure all its systems are operating at full capacity. First and foremost, air defense, which will react to anything that looks like a response on any scale, and the Military Intelligence Directorate and the Mossad, which will have to make an unprecedented effort ahead of any strike, collecting not only information about the Iranian nuclear program but also tactical and operational intelligence that will allow it to strike effectively.

While all this is happening, Israel's ground forces will have to be on the highest alert, ready for the possibility of a war in the north or with Gaza, or both, all without leaving any signs. They will have to up the preparedness of various units, step up drills, and supply missing equipment. It's not easy to do all this in secret. Leading up to the attack on Syria's reactor, the army was forced to adopt trickery in order to prepare for a possible Syrian response. Syria opted not to respond, but the Iranians might behave differently.

It takes time to make all these preparations. The IDF is waiting for four Boeing KC-46 Pegasus aerial refueling aircraft, but it could take years for them to arrive, and the Americans are refusing to let Israel jump the line and deliver them sooner. It will also take months to refill the warehouses with Iron Dome interceptor missiles and other IAF precision equipment.

A decade ago, the IDF would have needed a few years to get ready. Then, too, it was impossible to shift the military into a state of immediate readiness, and when it was put into attack mode – and that happened a few times – the directive was for it to be ready within 16 days of the moment the political leadership gave the green light. At the time, the IDF wanted to cut down the preparation time as much as possible, because it kept it from other activities and also because it came at a heavy cost to the economy. Ashkenazi would say that "In every round of preparations, El Al is half-grounded, because its pilots are on reserve duty with me." That was true for other systems, as well, some of which have been bolstered since then – namely, military intelligence and cyber.

All the preparations will have to be done in secret. "The issue of information security is dramatic in an event like this," said a high-ranking reservist officer. "We've never handled a challenge like this, and it's not clear if it's even possible to keep a secret like this for long."

Keeping things secret will be a problem not only for the IDF and the defense establishment (the Mossad is an integral part of this mission, as well as the Israel Atomic Energy Commission and parts of the Defense Ministry), but also – and mainly – the government. Such a dramatic decision would need to be approved by the cabinet and the Opposition leader would need to be informed. This is what Menachem Begin did prior to the attack in Iraq when he informed Opposition leader Shimon Peres of the plan. Ehud Olmert also informed Netanyahu ahead of the attack in Syria.

In this case, the cabinet will be frequently updated about preparations, and give the IDF authority to prepare for the operation. Only when the attack is imminent will the cabinet be asked to approve it. A very small group will decide on the final timing – the prime minister, the defense and foreign ministers, and possibly another minister, Lieberman, as a nod to his seniority and his status as a former defense minister.

Anyone let in on the secret at any stage will be asked to sign draconic confidentiality papers. All officials will be ordered to keep it secret and it will be made clear that anyone who lets it out will face severe punishment.

Even before a final decision on an attack, Israel will have to decide on its red lines. It will have to define them not only for itself, but also for the world. It will have to build international legitimacy for action. Without that legitimacy, a strike could have negative results and put Israel in the position of the aggressor, while giving Iran legitimacy to return to its nuclear project. In this case, Iran will argue that because its "nuclear research project" was attacked by a nuclear nation, it has to develop nuclear weapons to defend itself from similar attacks in future. Israel would find it difficult to thwart that a second time.

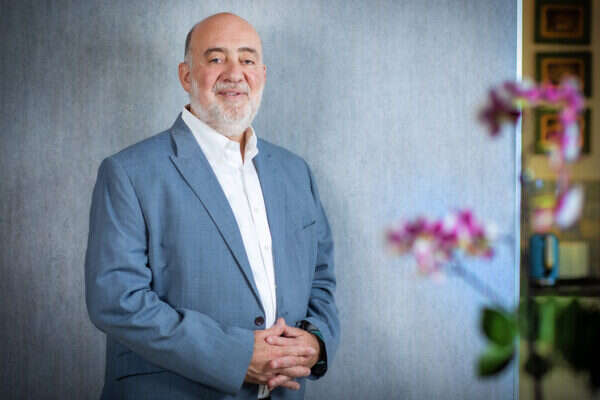

Former Israeli Ambassador to the UN Ron Prosor says, "Building legitimacy in the world is complicated, because it's hard to do without exposing the operations, which would put the attack at risk."

"We need to explain to the world not only why it's vital to stop Iran, but also that an action like this could hold it back for years," he says.

"It requires precise diplomatic preparatory work, which is also hard to do without giving anything away. The diplomats at the Foreign Ministry need to be in the loop, but none of them will know why, and certainly not when. The Mossad, the IDF, and the National Security Council will be responsible for delivering information. We can only work in full coordination with the Americans, both in terms of the military and diplomacy," Prosor adds.

"With everyone else – the Russians, the Chinese, the Europeans, the Gulf States – we need to prepare the background. Take them step by step, explain why Iran is so complicated and warn them about what will happen if Iran becomes a nuclear threshold state, or heaven forbid, a nuclearized state."

This process will have to work differently in every country. With the British and French, for example, Israel has intelligence agreements that allow a certain amount of material to be shared. It's likely that Israel will share some information with the Gulf states, as well, especially to enlist its new partners (and the ones that are still in the closet) to stand by its side on the day of the attack and during whatever follows.

"Coordination with the Americans is strategic, it's at the core of our interest," says the senior IDF official. "They can give us lots of help in the attack itself – for example, intelligence or radar support, which are deployed in Iraq and the Persian Gulf, and even search and rescue capabilities, and of course, in providing us military protection after the attack."

As part of the new plans being drawn up now, the IDF is also preparing for the possibility to attack without coordinating with the Americans.

"We don't need a green light from them, but it would be good if there were an understanding, an amber light, mostly so we don't surprise them," a former senior defense official says. "So this attack should come after the Americans despair of ever reaching a nuclear deal with the Iranians."

As noted, the Americans controlled Iraq in 2010, and Israel needed to coordinate with them down to the smallest details in order to carry out a strike in Iran. This is no longer the case, but the Americans still have a significant presence in the region that could help Israel. It's unlikely that they will offer Israel use of their air bases in Qatar or their naval base in Bahrain, and there's no chance that any Arab state would agree to openly cooperate with Israel, exposing itself to a retaliatory attack by Iran. But localized, secret cooperation is a possibility, from helicopters to search and rescue services, to setting up various detection and interception systems.

Because of the Arab boycott, until the start of this year Israel fell under the US European Command (EUCOM), even though it operated in the Central Command's territory, which necessitated complex coordination. After the Abraham Accords, Israel was moved to CENTCOM, which makes things simpler and creates a space for cooperation – starting with ongoing updates about strikes in Syria, to joint military drills.

Preparations for an attack will require Israel to carry out frequent war games. It will have to practice every possible scenario on every front, and make sure that the political leadership is present. Our leaders don't like this, as they would prefer to leave themselves as much room to maneuver as possible and not show ahead of time what they will do in any given scenario. So the drills used various "former" officials to play the role of prime minister. When it comes to Iran, our political leaders would do well to show up in person and prepare for the day they will have to give the order and the ramifications of them saying "Go."

The stage of the attack itself requires, first of all, a decision about what the targets are. The range of possibilities is almost endless – localized strikes on uranium enrichment facilities, strikes on any facility linked to the nuclear program, or an all-out attack that would also target missile launchers and Shahab missile manufacturing sites, cruise missile launching sites, facilities of the Iranian Revolutionary Guards Corps, and more.

"The backbone of the [Iranian] nuclear program is the enrichment facilities at Qom [Fordo] and Natanz," says the senior IDF officer.

Aside from these sites, Israel can also attack factories around Tehran that manufacture centrifuges, the uranium conversion facility at Isfahan, the heavy water reactor at Arak, and the experimental site at Parchin. It will also be necessary to destroy the air defenses around all of these sites.

Most experts think that the operation will have to focus only on the core of the nuclear program and its enrichment sites: "Make it clear to them that this is what we insist on, and that we have no interest in a full-scale war," the former defense official says. "But if they respond – we'll take the rest, too."

Israel would prefer to carry out a strike like this in a single shot, which is why it would prefer that the Americans do it. They could attack, assess the damage, and go back the next day and the day after if necessary. Israel, however, is extremely limited because of the distance, its number of planes, and its need to defend itself against a response from multiple fronts the moment it attacks.

Some officials think that Israel should take advantage of the opportunity of an attack to eradicate as many of Iran's capabilities as possible – and especially try to destabilize the regime through an attack on the IRGC. But that scenario is unlikely. Conversations with many defense officials past and present leads one to conclude that Israel would prefer a more focused action.

In the future, Israel should have additional capabilities, but in the near future, it will depend on its abilities to carry out an airstrike on Iran. It would be a complex strike involving hundreds of aircraft. Presumably, the first planes to arrive in Iran would be the F35 stealth fighters, which would destroy Iran's air defenses. Then F15s and F16s would arrive, with the various weaponry they can carry and fire.

The main factor is what each aircraft can carry for the requisite distance: the more fuel the plane is holding, the less weapons it can carry, and vice versa. So there will be a need for mid-air refueling, as well as decisions about what plane to send in to leave enough to defend Israel's own skies. There will also need to be precise plans about the kinds of ammunition to be used, the angles of attack, and the strikes on targets, especially underground ones. Of course, the selection of the combat pilots to fly the mission will be especially careful.

"Everyone dreams of taking part in a mission like this. There will be a war between the pilots about who gets to be there," a veteran pilot says.

We can assume that the airstrike will be accompanied by search and rescue forces in helicopters and on the ground, who will have been flown in secretly ahead of time or moved in on ships. Naval forces will also be moved toward the Gulf. Other aircraft will have to provide air coverage over a distance of 1,300 km. (807 miles) or more.

There is no expectation that this attack will go smoothly, like the ones in Iraq or Syria. It's not only that Iran is much better defended, but also that an operation like this will inevitably face problems because of the enormous number of aircraft taking part in it. Planes could go down because they are hit or malfunction, and pilots could have to abandon their planes over enemy territory and be taken prisoner.

Pilots will have to undergo complicated mental preparation, far beyond the usual, as will those who send them on the operation. The political leadership will probably ask the IDF for a probable casualty count, as well as the projected number of wounded in Israel as a result of an Iranian response. But even if the numbers are high, it's unlikely that they would cause any leader in Israel to ignore Iran's attempts to acquire nuclear weapons.

It will be complicated to reach Iran by air. You don't need to be an expert to analyze the flight routes and possibilities: supposedly, all of Iran's neighbors – including Turkey – have an interest in working with Israel, given their common concerns about Iran. But it's doubtful they will want to be exposed as having allowed Israel to use their airspace to attack Iran. This is particularly true of Jordan, Saudi Arabia, and the Gulf states, and to a lesser degree Azerbaijan, which also shares a border with Iran. The IAF will know how to overcome this difficulty from an operational perspective and fly unseen (certainly on the way out), but this is another reason why extensive diplomatic preparations are necessary to create legitimacy and understanding so Israel can use a certain country's airspace en route to attack without having problems with it later.

An airstrike will probably not be able to destroy Iran's underground nuclear facilities. It's possible that some will require ground forces, which would go in secretly and plant materials that would make it possible to target the sites in the strike. This element significantly adds to the planning and problems of execution. There are a number of ways into Iran, but it's a huge country, difficult to get around, certainly when one has to do so covertly. The Americans will testify to this – they learned in 1980 when they landed for their failed attempt to free the hostages being held in Tehran.

The former defense official notes that "If we attack and delay Iran's nuclear program by a year or two, it's as if we did nothing. We need to be sure that significant damage is done and we'll put them off [nuclear weapons] for many years."

There are many officials in Israel who think that given the state of Iran's nuclear program, the mission is too much for Israel, and only the Americans (or the Americans with Israel) can pull it off. Others think that Israel can carry out an effective localized strike that will deal a blow to one aspect of Iran's nuclear program, but won't destroy it entirely. In making the decision, Israel will have to weigh not only the results, but also the ramifications: "the day after." Here, too, the range of possibilities is nearly endless, from the Iranians ignoring it to an all-out war in the Middle East.

In 2010, the US warned that an Israeli attack on Iran would lead to a world war. The Americans were mostly bothered by the price they would pay, which they claimed would entail a US ground incursion into Iran to stop it.

Yadlin says, "I thought then, and I think now, that there won't be a world war, or even a regional war. Even if there is an Iranian response against Israel, it will be moderate, and even if it causes damage, it won't be the end of the world. We certainly won't see another sack of Jerusalem here."

Supposedly, the Iranians have three possibilities: a full-out response, a partial response, or no response. Middle East scholar Professor Eyal Zisser of Tel Aviv University thinks that there will be a response from Iran.

"If they don't respond, it will send Israel a message that it can keep attacking them without interference, like it does in Syria. The attacks on oil tankers in the past two years proved that the Iranians aren't sitting quietly. They respond. Otherwise, why have they been making threats all these years and building their forces? They can attack us, or our allies, or both," Zisser says.

The Iranian decision will to a large extent be dictated by the extent to which the Americans back the attack.

"Iran can't risk a war with the US," the IDF official explains. "Even after Qasem Soleimani was killed, they made due with a symbolic firing of 16 rockets at the American base in Dir a-Zur, and that was only after they made certain that no soldier would be killed."

Shine also thinks that the Iranians will respond, "but if the US is behind us, it will be completely different. This isn't the Syrian nuclear reactor, which was built secretly and no one knew about. Everyone knows about Iran, and it won't go unnoticed. Iran will have to decide whether or not to respond from its own territory, on its own, or through its satellites."

Thus far, Iran has avoided launching open attacks from within its borders. It's not that it doesn't – the massive strike on Saudi Arabia's Aramco oil facility in September 2019 was secretly launched from Iran. Recently, Defense Minister Benny Gantz revealed cruise missile bases that the Iranians maintain at Kashan, north of Isfahan. That facility and others are operated by the IRGC Aerospace Force under the command of Ali Hajizadeh, whom Israel has already marked as the most problematic official in Iran after Soleimani was killed in a US drone strike two years ago.

Iran can act on its own, even fire Shahab missiles at Israel. It has hundreds of them, and some might even have been fitted out with chemical warheads. It can also take action via its satellites: the Houthis in Yemen have precision capabilities, including long-range attack drones, as do some of the militias in Iraq, which have already used drones against US military bases.

Israel's main concern will be how Hezbollah will respond. Will it launch a war, be satisfied with a symbolic response, or sit on the fence? This is a critical issue, and experts don't agree about it.

"Hezbollah was built up and prepared precisely for this, and we can assume that it will use everything it has against us," Shine says. Zisser, on the other hand, thinks that Hezbollah will want to avoid a full-scale war.

"[Hezbollah leader Hassan] Nasrallah will try to stay out of it. He might respond here or there, but it will depend on how much pressure the Iranians put on him. He might be satisfied with a symbolic response, to do his duty, and nothing more," Zisser says.

The other side isn't the only one that will face tough decisions. Israel, for example, will have to decide whether or not, after an attack on Iran it will want to carry out preemptive strikes against Hezbollah's various sites, especially those linked to the group's precision missile program. The advantage of strikes like these is that they can take out specific capabilities that threaten Israel. The disadvantage: it will surely start a war with Hezbollah, and turn the strike on Iran into a war in the north.

Most experts think Israel will avoid doing that. It will send Hezbollah clear warnings that the attack was directed at Iran's nuclear program, and if Hezbollah keeps quiet, that will remain its only goal.

"If we do otherwise, if we take massive action in Lebanon, Hezbollah will respond significantly," Zisser says. "But if we act wisely, even its responses will be moderate, because they have no interest in the IDF taking a few divisions and invading Lebanon."

The senior IDF official also thinks that Hezbollah won't rush to demolish Lebanon for Tehran's sake. "Nasrallah is a Lebanese patriot. He'll respond, but moderately. Assuming that the main target of the whole event is Iran's nuclear program, Israel should even accept some 'stings' from him, even a few casualties, and ignore it, to avoid a widespread conflict in the north."

Yadlin also thinks that Hezbollah will keep itself in check, "But if it chooses to respond, it would be better for us to take action now, before it's defended by Iranian nuclear weapons."

A war in the north, on any scale, will require Israel to call up massive forces, which will hinder its ability to wage an ongoing battle against Iran. It will certainly need to equip itself ahead of time with tens of thousands of Iron Dome and David's Sling interceptor missiles, only a small part of which have been agreed on and are due to arrive bit by bit in the next few years. This is in addition to the need for Arrow missiles to intercept long-range missiles. All this will cost billions, and only part of it is in place (and that was thanks to special US aid). For years, the IDF has been screaming that the country's air defenses fall far short of what is necessary, given the threats, and need massive restocking.

It's likely that Iran will also prod Gaza to respond. The Palestinian Islamic Jihad already cooperates with it, and so does Hamas, to some extent. It could also try to attack Israel's weaker allies, like the Gulf states, or Israeli interests there. It will certainly try to attack Israelis, and Israeli and Jewish interests all over the world.

At the same time, Iran will take diplomatic action. "It will turn to its allies, especially Russia and China, and argue that Israel is the aggressor and ask for protection," Zisser says. "It might also use [the attack] as an excuse to try and return to its nuclear project, this time in the position of the one who needs protection against Israeli aggression."

Therefore, Israel has to do everything so that the attack is as effective as possible, and if the first wave doesn't succeed – attack again, despite all the complications this would entail. This comes as a possible cost of an open war with Iran in which the two countries trade blows every so often. The IDF is also preparing for this possibility as part of its new plans. When they are in place, Israel should be ready for an all-out war with Iran, and not only isolated strikes on its nuclear project.

None of this is expected to happen in the next few days or weeks, and probably not even the next few months. As long as the Iran nuclear talks are underway, and the US is reaching out to Iran diplomatically, an attack would be out of bounds because Israel would be accused of torpedoing the talks and its allies would turn on it, including Washington, which has already made it clear that it expects "zero surprises" at this time. Israel has no commitment to this, but won't act without coordinating with the Americans. That's what it did a decade ago, to avoid a conflict with the US that could have ramifications much broader than the Iranian issue.

This "down time" is good for Israel. It can use it to try and influence the American (and European) moves and the nascent deal, while at the same time stepping up its military preparations, completing its plans, building models and equipping itself in order to reach a higher level of operational readiness.

And when all this is done, if it

turns out tomorrow that Iran lied to the world and is closer to a

nuclear bomb than we thought, the decision-makers will have to decide

whether or not to attack immediately. As always, it would be better if

the Americans – who promised that Iran would never have nuclear

capabilities – did it. But if the IDF takes charge, it will take several

long weeks of preparation before an operation like this can get off the

ground, less than optimally ready and with less certainty of success.

Yoav Limor

Source: https://www.israelhayom.com/2021/12/17/what-the-public-doesnt-know-about-an-attack-on-iran/