by Dr. James M. Dorsey

-- statements in recent years by some Saudi

leaders and US officials – suggested that regime change was on their radar.

BESA Center Perspectives Paper No. 1,113, March 15, 2019

Officially, both Saudi Arabia and the US, which

withdrew last year from the 2015 international accord that curbs the

Islamic Republic’s nuclear program and imposed harsh economic sanctions,

are demanding a change of Iran’s regional and defense policies rather

than of its regime.

Yet statements in recent years by some Saudi

leaders and US officials – as well a string of declarations at the

recent US-sponsored Ministerial to Promote a Future of Peace and

Stability in the Middle East in Warsaw by officials of the Trump

administration, as well as Saudi Arabia, Israel, the United Arab

Emirates, and Bahrain – suggested that regime change was on their radar.

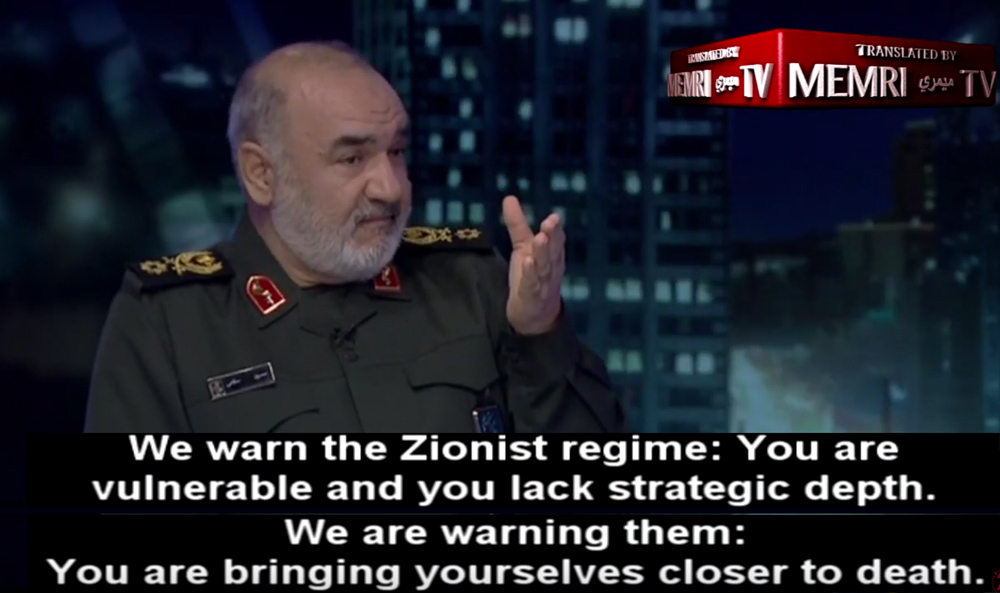

President Donald Trump’s hard-line national

security advisor John Bolton, a past advocate of regime change and a

covert war to destabilize Iran, concluded an outline on the White

House’s official Twitter account of Washington’s long list of grievances

and accusations levelled at Iranian leaders by addressing Supreme

Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, directly. “I don’t think you’ll have too many more anniversaries,” Bolton said, as Iran celebrated the 40th anniversary of its Islamic Revolution.

Multiple indicators bolster the notion that the

real goal of Saudi and US policy is regime change, prompted by the

sanctions and a destabilization campaign that would foster unrest among

Iran’s ethnic minorities.

However, Saudi Arabia’s announcement that it

will invest US$150 billion to enable it to export three billion cubic

meters of gas a year by 2030 suggests that imminent regime change may

not be in the kingdom’s immediate interest.

Viewed through the lens of the timeline of Saudi

Arabia’s gas plans, the kingdom is likely to benefit more from an Iran

that is isolated and weakened for years to come, which would give Riyadh

time to get up to speed on gas. That would serve Saudi Arabia’s gas

plans better than an Iran that returns to the international fold under a

new, more accommodating government. A potential destabilization

campaign that is low-level and intermittent but not regime-threatening

would serve that purpose.

It would also extend the window of opportunity on

which Saudi Arabia relies to assert regional leadership. That window

remains open as long as the obvious regional powers – Iran, Turkey, and

Egypt – are in various states of disrepair. Punitive economic sanctions,

international isolation, and domestic turmoil serve to keep Iran weak

and unable to leverage its assets.

The emergence of Saudi gas plans appears to put

the kingdom’s strategy towards Iran at cross purposes. If Saudi Arabia’s

gas-driven interest is prolonged containment of Iran, operations at the

Indian-backed Arabian Sea port of Chabahar were believed to have given

the effort to achieve a change of Tehran’s regional and defense policy,

if not its regime, a sense of urgency.

Written by Mohammed Hassan Husseinbor, identified

as an Iranian political researcher, the study warned that Chabahar posed

a threat because it would enable Iran to increase its market share in

India for its oil exports at the expense of Saudi Arabia, raise foreign

investment in the Islamic Republic, increase government revenues, and

allow Iran to project power in the Gulf and the Indian Ocean.

In December, India started handling the port’s

operations, and Pakistani analysts now expect around US$5 billion in

Afghan trade to flow through Chabahar. It could also further strain ties

with Pakistan, which accuses India of fomenting nationalist unrest in

Balochistan. India and Pakistan are on the brink of a potentially

escalating military conflict over Kashmir.

The perceived threat of Chabahar pales, however,

against the opportunity that Saudi Arabia’s ability to be a major gas

exporter would open up.

In a study published in 2015,

energy scholar Micha’el Tanchum suggested that it would be gas supplies

from Iran and Turkmenistan, two Caspian Sea states, rather than Saudi

oil that would determine which way Eurasia’s future energy architecture

tilts: towards China, the world’s third-largest LNG importer, or towards

Europe.

With 24.6 billion cubic meters potentially

available for annual piped exports beyond its current supply

commitments, Iran, unfettered by sanctions and with no Saudi

competition, could emerge as Eurasia’s swing producer, which would

significantly enhance its regional clout.

The departure of Zarif, a suave, US-educated

moderate who was Iran’s main negotiator of the nuclear accord, would

have enhanced the quest of Saudi Arabia and its allies even if their

timelines for a change of Iranian policies, if not of the regime,

differ.

His continued tenure as foreign minister is likely

to encourage Europe, China, and Russia in their efforts to salvage the

nuclear deal but do little to change Saudi or US long-term strategy.

Tweeted US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo: Zarif “and @HassanRouhani are just front men for a corrupt religious mafia.

We know @khamenei_ir makes all final decisions. Our policy is

unchanged—the regime must behave like a normal country and respect its

people.”

Dr. James M. Dorsey, a non-resident Senior Associate at the BESA Center, is a senior fellow at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies at Singapore’s Nanyang Technological University and co-director of the University of Würzburg’s Institute for Fan Culture.

Source: https://besacenter.org/perspectives-papers/saudi-gas-export-plan/

Follow Middle East and Terrorism on Twitter