by Seth Frantzman

The key -- is to close the gap that potentially exists near the ground.

Iran's September 14 attack on Saudi oil facilities highlights the threat posed by swarms of drones and low-altitude cruise missiles.

|

Now, in a region where that threat is particularly acute, countries are left to reexamine existing air defense technology.

According to the Saudi Defense Ministry, 18 drones and seven cruise missiles were fired at the kingdom in the early hours the day in mid-September.

The drones struck Abqaiq, a facility that the Center for Strategic and International Studies think tank had warned the month before was a potential critical infrastructure target. Several cruise missiles fell short and did not hit the facility. Four cruise missiles struck Khurais. Saudi and U.S. officials put blame on Iran, but the government there denies involvement.

Smoke billows from an oil-processing facility in Abqaiq, Saudi Arabia, following the September 14 attack.

|

The Abqaiq facility's air defenses reportedly included the American-made Patriot system, Oerlikon GDF 35mm cannons equipped with the Skyguard radar and a version of France's Crotale called Shahine. Satellite images posted by Michael Duitsman, a research associate at the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies, shows the setup: Impeded by radar ranges and the facility itself, as well as the speed and angle of the drones and missiles, Saudi air defense apparently did not engage the drones.

"If U.S.-supplied air defenses were not oriented to defend against an attack from Iran, that's incomprehensible. If they were, but they were not engaged, that's incompetent. If they simply weren't up to the task of preventing such precision attacks, that's concerning," said Daniel Shapiro, a former U.S. ambassador to Israel and a visiting fellow at the Institute for National Security Studies. "And it would seem to validate Israeli concerns that even effective air and missile defense systems, as Israel has, could be overwhelmed by a sufficient quantity of precision-guidance missiles."

Daniel Shapiro: The September 14 attack "would seem to validate Israeli concerns that even effective air and missile defense systems ... could be overwhelmed by a sufficient quantity of precision-guidance missiles."

|

Uzi Rubin, former director of the state-run Israel Missile Defense Organization, doesn't think what happened in Saudi Arabia could happen in Israel. "We have a smaller area, and that has an advantage in many respects because it is an advantage in controlling our airspace."

The challenge in stopping an attack like September 14 is detecting low-flying threats, not shooting them down.

|

The key, then, is to close the gap that potentially exists near the ground.

"It's not too difficult to close the gap; the Saudis can do it with local defenses," he asserted. But he acknowledged that the larger the land area, the more difficult it can be to maintain control.

Rubin said shooting down drone swarms can be accomplished with anti-aircraft guns, noting that Iraq downed several Tomahawk cruise missiles in 1991 after discovering their flight path.

"You don't need anything fancy," he said — the Russian SA-22 or Pantsir system, with 30mm cannons, missiles and infrared direction finders would do.

"I think once the surprise of the [Sept. 14] attack wears off, then one should sit back and see it is not a very devastating attack." Like Yungman, he said a long-range precision missile aimed at a strategic facility like a nuclear reactor in a European country would be a more serious threat.

Thomas Karako: "The specter of complex, integrated air and missile attack ... [is] not a technological problem, it's an engineering problem."

|

He argues that the Abqaiq attack draws a "bright red line under the problem set" and that "we need a mix of active and passive measures, kinetic and non-kinetic to counter."

"It's not a technological problem, it's an engineering problem," he said. "You need to look beyond the horizon and look in every direction." That would include 360 coverage by radar and elevated sensors.

Israel, the Test Bed

Yungman considers the Middle East, particularly Israel, to be a proving ground. Since the 1940s, a number of different weapons systems, many made in Western countries or the Soviet Union, were used in regional combat."In this region, the asymmetric threat became bigger. So in the north there are almost 200,000 short-range rockets and missiles and accurate missiles as a threat" from Hezbollah, he said. "And in Syria we can see accurate, maneuvering ballistic missiles and cruise missiles. So air defense and air missile defense became, from the asymmetric aspect, bigger and bigger, and the air defense system became an issue we need to invest in and develop as fast as we can."

With the support of the United States, Israel built and tested the Arrow system in the 1990s, becoming one layer of the country's multilayered system that eventually included Arrow-2, Iron Dome and David's Sling.

Short of using preemptive airstrikes against drone manufacturers and launch teams, Israel is upgrading its air defense on a "daily basis," Yungman noted.

"The main threat is not face-to-face [combat] threats — it is rockets, drones, cruise missiles, maneuvering [theater ballistic missiles] and [short-range ballistic missiles] with big and small warheads. When we are talking about thousands or tens of thousands or more, it is very complicated, but it can be defeated," he said.

Soft-kill measures involve jamming a drone's GPS or radio controls.

|

But Rubin said what stands out about the Abqaiq incident is that the homing by the drones appeared to be optical, not GPS-guided.

Also noteworthy, evidence indicates that some of the UAVs weren't carrying warheads, as they didn't all explode.

Alternatively, a hard-kill approach might involve using a 5- to 10-kilowatt laser. Lasers can destroy drones up to 2.5 kilometers away, according to Yungman.

Hard-kill measures involve physically destroying or disabling an incoming drone.

|

"I can say that from 2 kilometers I could hit a drone the size of a penny," Yungman claimed.

Another option could be drone-on-drone combat, though that capability is still under development.

While systems like the Iron Dome are combat-proven, questions remain about their ability to confront a drone swarm.

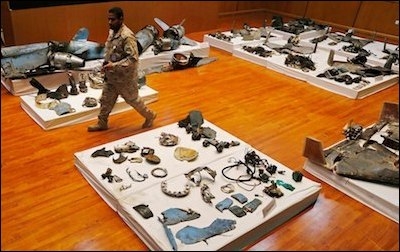

Remains of Iranian cruise missiles and drones used in the September 14 attack

|

"In our research and technology we have the radar and electro-optical and jamming, GPS-denying [capabilities]," Yungman said. "And we have the ability to kill it."

Rubin described the attack on Saudi Arabia as a kind of "Pearl Harbor," and it reminded him to an Aug. 17 attack on the Shaybah oil field in Saudi Arabia by Houthi rebels involving 10 drones.

"The surprise was not in the attack, but the audacity," Rubin recalled, adding that a precision attack by drones doesn't make the aircraft less vulnerable to air defense systems.

The Stunner interceptor missile of David's Sling, for instance, has the capability to intercept drones, missiles and other ordnance, including low-flying cruise missiles. But for that to work, there can't be a gap in the radar coverage, Rubin noted.

Certainly, the recent attack in Saudi Arabia will impact industry and spur development from the key players in this area of defense, according to Karako of CSIS.

"I think you'll see global demand signal for a variety of means to counter these threats," he said. "It will spark a lot of solutions."

Seth Frantzman, a writing fellow at the Middle East Forum, is the author of After ISIS: America, Iran and the Struggle for the Middle East (2019), op-ed editor of The Jerusalem Post, and founder of the Middle East Center for Reporting and Analysis.

Source: https://www.meforum.org/59453/can-air-defense-systems-stop-drone-swarms?utm_source=Middle+East+Forum&utm_campaign=7505636ea9-MEF_Frantzman_2019_10_02_07_43

Follow Middle East and Terrorism on Twitter

No comments:

Post a Comment