by Akiva Bigman

Hat tip: Dr. Jean-Charles Bensoussan

An Orthodox Jew from Manhattan, William Brickman never expected to be dispatched to Germany during World War II. There, posing as an SS officer behind enemy lines, Brickman's job was to catch Nazis attempting to flee Germany for South America.

|

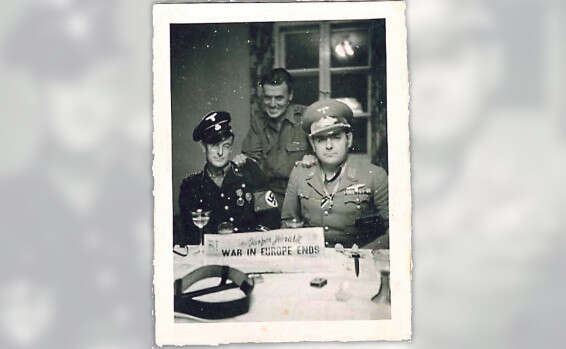

| William Brickman, far right, with his fellow agents in Nazi uniform |

Haim Brickman was just 5 years old when he learned that his stepfather had been a Nazi officer. It was the 1960s, and the newly blended family had just relocated to the Philadelphia suburbs for Haim’s stepfather William’s, academic career. While rummaging through some boxes in the basement, Haim discovered an SS uniform, officer insignia, Nazi flags, documents in German and worst of all, a picture of his father in full Nazi uniform.

Shocked at what he had found, Haim ran up the basement stairs, his mind racing. “Could my mother have unknowingly married a Nazi?” “What else is he hiding from us?” “What crimes was he involved in?” Panting and out of breath, Haim entered the kitchen and yelled out, “Mommy, Daddy is a Nazi!” Haim’s mother smiled. That was the moment when he learned his family’s big secret.

Haim is my uncle. I have known about his stepfather for a few years now, and every year I am reminded of his past on Holocaust Remembrance Day. This year, though, I decided to look into the matter. Over the past few weeks, I have been collecting countless documents from personal archives and a few institutions in Israel and the US. Naturally, not everything was preserved in full. Some of the stories lack detail, while in other instances, there are discrepancies between the various documents and Haim’s childhood memories. But nevertheless, what I have been able to learn makes a fascinating and inspiring story.

This is the incredible story of William Zeev Brickman, a professor of education, American spy and an emissary behind the Iron Curtain.

William Wolfgang Brickman was born in June 1913 in Manhattan, the son of Shalom-David, a German Jew, and Lahia-Sarah, a Jewish woman originally from the Polish town of Jedwabne, the infamous site where the Polish locals murdered their Jewish neighbors.

As a member of an Orthodox Jewish family, Brickman mostly spoke Yiddish at home, while he learned English and other languages out on the street. His father died when he was young, apparently the result of a self-inflicted umbilical hernia aimed at helping avoid the military draft back in Europe.

William was a towering, vibrant boy. When he registered for college, he decided to play it safe and major in something he knew he would be good at. With a background in German and Yiddish, he decided registered for the German and education programs at the City University of New York.

Agent 004

During the 1930s, Brickman got his doctorate in German, Latin and education, managing to overcome the hostility and often anti-Semitism of some of the academic staff. His knowledge of Yiddish from home and knack for languages in general allowed him to develop great expertise in a number of languages, including full mastery of various local dialects. According to his academic resume, he could read 20 European languages, in addition to Latin and ancient Greek, three Asian and two African languages.

By the late 1930s, Brickman had a blossoming academic career, but World War II broke out and threw a wrench in his plans. In March 1943, one year after the US entered the war, he was drafted into the air force as a historian and German-language expert. In a letter of recommendation for an officers’ course, Brickman’s direct commander at his base in Fort Worth, Texas described him as “a scholar turned soldier, who proudly made the transition from civilian to military life.”

Brickman had requested to be drafted as an officer in the air force’s medical or chemical warfare units. All signs point to him having been convinced the war would serve as a sort of continuation of his academic career, but once again, fate would have other plans.

In late 1944, following the allied invasion of northern France, it was clear the demise of the Third Reich was a matter of time. The US military was on the lookout for German speakers, when Brickman’s name came up. He was summoned to interviews that were presented to him as ascertaining whether he would be a good fit for the occupation forces in Germany after the war. Brickman was supposed to serve in the occupation forces’ postal service, where his knowledge of German would be considered an advantage, they said. He scored high marks on the language exams, and of course, was accepted for the role. Though he did not know it at the time, his peaceful life was about to get a lot more interesting. A few weeks later, when he received his new draft order for his unit, it was clear to Brickman that the war was going to be an entirely different experience for him than he had expected.

According to the military documents, Brickman was to be stationed with the US Counter Intelligence Corps 970th division, which operated in liberated territories in order to catch Nazi agents that had stayed behind. Between Jan. and Feb. of 1945, Brickman took an intelligence course at the Fort Ritchie base in Maryland, in preparation for his being stationed in liberated Germany. According to his son Haim, at this stage, there was yet another change in plans and Brickman was drafted to the Office of Strategic Services, the US intelligence agency that would later become the CIA.

At first, Brickman was alarmed. Beyond the challenges of being stationed overseas, he did not want to leave his mother, who was alone and suffering from a serious illness, behind. As an Orthodox Jew, he also feared that on such a mission, he would not be able to maintain his religious way of life. Nevertheless, Brickman would soon be identified as Agent 004. Later on, his relatives would joke that Brickman had in fact preceded Agent 007, otherwise known as James Bond.

Setting the trap

Service in the OSS was particularly challenging, and Brickman’s unit was to be stationed inside Germany, behind enemy lines, in the twilight of the Third Reich. Their objective: to capture senior SS officers that tried to escape and evade capture. The plan was to parachute into the border area between Germany and then-Czechoslovakia – an area known for being a center where Nazis would head in order to flee the country, in particular to Argentina, and pose as senior officers to catch those attempting to flee. For reasons that remain unclear, instead of parachuting in, the forces crossed the border by foot, setting up camp in Regensberg, Germany. This was made easier by the fact that the allied forces had already made significant progress, and the battle for Berlin was already in its advanced stages. The Germans began to destroy documents and archives, and the chaos that pervaded made it impossible to check the identities of agents posing as Nazi officers, thus allowing them to carry out their missions.

The official military documents I found while researching this article do not add any information or details about this period. All I know is what Brickman himself said about this time in conversations with his stepson. As Brickman told it, his unit offered Nazi officers a way out of the country, interrogated them and then foiled their escape plans. Their working assumption was that the only people in the area with the means and desire to leave Germany would be senior officers in the SS and the Wehrmacht.

Their method went something like this: Some of the agents in the unit would go out in public, mainly to the bars the Nazi officers were known to frequent. After having given the appearance they had been drinking, the agents would begin to brag about about how they could help those who had the money flee the country for South America. When someone would turn to the agents and ask for their help, they would direct them to a specific cabin, where the agent would say they would find a Nazi officer with the connections and ability to get them out of the country. The Nazis would arrive at the cabin at night, where they would be greeted by a secretary who would ask them a few questions about where they served, their ranking and the like. The secretary would then call Brickman, who would be waiting in the office inside.

Brickman would be dressed in SS fatigues, on his shoulder the insignia of a military rank higher than that of his guest.

According to Haim, his stepfather “made sure not to take things too far. He wanted to remain credible, but he wanted to be more senior than the Nazi in order for him to obey him and treat him with respect.”

In his conversation with the Nazi, Brickman would investigate the officer over his actions in the war and the places where he had served, before agreeing on a payment for his evacuation. Eventually, Brickman would send him a rendezvous point on the Czechoslovakian border and an agreed upon date when a group would prepare to leave for South America. When that date arrived, the Nazi officers would show up to the meeting point. But instead of finding their guides for the trip out of the country, they would find other OSS officers, who would take them hostage and transfer them to allied prisons. Other senior officers were taken to Nuremberg.

In one case, Brickman’s unit had received information about the presence of very high-ranking SS officer in one of the villages in the area, and the agents set out to arrest him. Brickman entered the room, gave him two minutes to pack before leaving. The officer protested, saying he had many possessions and needed more time. Brickman made it clear that if he was not be ready, he would be arrested and dragged through the streets naked. Two minutes later, the officer was ready.

Brickman was involved in a mission to catch Martin Berman, one of the heads of the German Nazi regime. While the allies suspected he was hanging around the Czechoslovakian border, there were no pictures of him available, so he could not be identified. Brickman arrived at the village where Berman was born and located the school he had attended as a boy. It was there he found a photograph of Burman, which he distributed to his fellow agents. According to Haim’s account, his father managed to get to the village where Burman had apparently been hiding, although he did not ultimately succeed in catching him.

After the war, Brickman went back to working with the Counter Intelligence Services, where he was made responsible for Germany’s Deggendorf district. When the Nuremberg trials began, he was stationed at one point with the security unit tasked with the area where the trials were held. In this role, a disguised Brickman would try to infiltrate the site in civilian clothes, with the aim of exposing weaknesses in the security system there. From time to time, when he would walk around among the Nazis’ cells, he would run into a prisoner he had helped capture. He would take the opportunity to remove his military hat and reveal his kippah underneath. “He wanted to show them that fate had been reversed, and the victims had become the masters,” Haim said.

In the months after the war, Haim would often serve as a witness at Jewish wedding ceremonies for concentration camp survivors conducted by a rabbi from the US military.

Brickman set himself a goal of collecting as many materials as possible from the Nazi era during his stay in postwar Germany, in order to preserve and document them for the sake of historical remembrance.

Among these documents, some of which are now at the Yad Vashem Holocaust memorial and museum in Jerusalem, others now housed in Brown University’s archives, one can find a collection of files and pamphlets from the Nazi era. There is also a copy of the Nazi party’s 1933 campaign platform, numerous Reichsmark bills, various limericks and everyday documents distributed by the regime. One of the more important findings that Brickman managed to take with him from Germany was an elegant album produced by the Gestapo that detailed the various torture methods used by the secret police. The album was donated to the Yad Vashem archives in 1960, along with uniforms, flags, pins, a collection of stamps and various other items from that period.

Postcards from behind the Iron Curtain

Upon his discharge from the army in April 1946, Brickman returned to the academic track. He studied with the well-known philosopher John Dewey, and during the 1950s, taught at New York University’s Department of Education, where he headed the department’s history program. In 1960, he transferred to the University of Pennsylvania, where he served as the head of the comparative education department.

Taking advantage of his knowledge of a variety of languages, Brickman’s research focused on the comparison of different education systems around the world. He wrote dozens of books on education, published dozens of articles in periodicals and Jewish magazines and edited a journal in the field.

In 1958, Brickman married Sylvia Mann, the daughter of a Jerusalemite family that had immigrated to the US. Mann was divorced with two children, Haim and his sister Simcha. It was in the early 1960s, when Brickman became a faculty member at the University of Pennsylvania that the family moved to that house in Philadelphia, taking with them William’s large collection of books and various objects that would expose Haim to his past.

According to Haim, William didn’t talk much about that time in his life. But Haim does recall how his stepfather would embarrass him whenever they would go see a James Bond movie together. “He would erupt in laughter in the middle of the movie. It really embarrassed me as a child,” Haim said.

Haim also recalled how his stepfather had refused to hire an attorney when he was called into court for some matter or another. “I underwent interrogation training, and I can get along just fine on my own,” William explained.

Just like at the outset of his military service, quite a few surprises were awaiting Brickman in his academic career. As an expert on comparative education fluent in world languages, the US State Department hired him to asses education systems around the world. It was the beginning of the aviation era and the status of the US was rising in the world, and America was contending with an influx of students coming to the country to get a higher education.

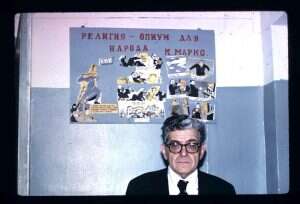

Of particular interest are his journeys to the Soviet Union, China and countries in Eastern Europe. On these travels, Brickman would not suffice with meeting senior officials in the nation’s capital and writing down the official version provided by the authorities, but rather would try as much as possible to tour the schools themselves and gain a first-hand impression of what was happening out in the field.

A troubled Jewish heart

While we don’t know whether Brickman was working for the intelligence service on these journeys, we do know for certain that he had developed an independent line of Jewish intelligence. After learning of the difficult situation the Jews in the Soviet Union faced, he began to bring religious articles and books with him on his trips and distribute them to members of the local community who were doing whatever they could, and at any price, to preserve their identity. Because the authorities would not check the contents of his suitcase upon entering the country, he could smuggle in large amounts of material. Upon departing, Brickman would take with him letters to the West, which he would conceal under a heavy pile of Soviet propaganda material, so that during the security check at the airport, no one would get suspicious.

In one of his reports, Brickman describes how he was almost caught. In Jan. 1972, while at the airport, waiting to depart for Leningrad, the decision was made to carry out a thorough check of his items.

“That was the first time my belongings were examined. They found a few copies of the Pravda newspaper, some writing by Karl Lenin, speeches by Brezhnev,” he said. As the officials seemed suspicious, Brickman showed them his library card for the Lenin Library and that made the necessary impression. I was allowed to continue in the direction of the bus.”

Brickman’s frequent journeys to the Soviet Union led him to connect with Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, who invested great efforts in preserving ties with the Jews in the Soviet Union at that time.

On one of his visits to Moscow, Brickman went to a synagogue on Friday night. Moscow’s Chief Rabbi Yehuda Leib Levin, who knew of his guest’s identity but feared the KGB agents planted in the crowd, gave a sermon in Russian in which he praised the authorities for supporting Jewish education, synagogues, religious institutions, and so on and forth. But in the middle of his speech, he looked directly at Brickman and under his breath, muttered the words of the kaddish, the mourner’s prayer. That was all it took for Brickman to understood that Soviet Jewry was on its deathbed.

Within the framework of his activity in the Soviet Union, Brickman forged ties with the Israeli Embassy in Moscow. One of the Pentateuch’s in William’s possession contains a special dedication from Ambassador Yaacov Sharett, the son of Israel’s second Prime Minister Moshe Sharett, dated the eve of Rosh Hashanah, 1960. The dedication reads: “To the dear, dedicated and brave Professor Brickman, in memory of many other Pentateuchs.”

Brickman died in the US in 1986, and was buried in Jerusalem’s Har Hamenuchot cemetery. He now has 25 great-grandchildren who reside in Israel. At his funeral, he was lauded for his contribution to Jewish education in the US and his efforts to obtain federal funding for Jewish day schools.

Akiva Bigman

Source: https://www.israelhayom.com/2019/06/15/a-jew-in-ss-uniform/

Follow Middle East and Terrorism on Twitter

No comments:

Post a Comment