by Neta Bar

Jere Van Dyk, a Pulitzer-nominated American journalist who was held captive by the Taliban says the group sees its struggle as one waged on a global scale and that Afghanistan under the Taliban's rule will be magnet for jihadis worldwide.

|

| Taliban fighters in Afghanistan | File photo: Reuters |

The sight of the Taliban marching victoriously in the Afghan capital, Kabul, caused shock and horror in the West. Almost as quickly as the government forces disintegrated in the face of the Taliban, journalists and pundits began to comment on the "barbaric masses" or the "illiterate army" that had vanquished a military trained by the world's greatest superpower and armed with modern weaponry and enormous budgets.

Indeed, Taliban fighters are part of rural and tribal Afghanistan, but if one shakes off cultural differences and Western arrogance, and dives deep into organization, a different picture emerges, one of a sophisticated network built up over decades and leaning on a combination of radical ideology, conceptual flexibility, and the ability to combine new and extreme political and religious ideas with centuries-old Afghan societal traditions.

The Taliban, which this week took over Afghanistan for a second time has its roots in scholarship. "The organization's name in Arabic means students," explains Aviv Oreg, an expert on Al Qaida and Islamist terrorism at the Institute for National Security Studies. "The name comes from the fact that the first Taliban recruits were Afghans from the Pashtun majority group that had fled fighting in the country and had been educated in Islamic madrassas in neighboring Pakistan."

"These students were assembled and trained by the Pakistani intelligence services, the ISI, one of the most significant and capable forces in the region, with the aim of increasing their control in Pakistan and Afghanistan." The recruits were led by veterans of the war against the Soviets, headed by Muslim religious cleric the Mullah Mohammad Omar.

Omar was born near Kandahar to a poor family. He was sent to be educated in a madrassa, a religious study institute, and joined the fight against the Soviet Union, but when the Soviet forces withdrew and the puppet communist government fell, he returned to his role as a religious teacher in Pakistan.

As chaos intensified within Afghanistan and the various mujahadeen groups fought each other and failed to reach any agreement on a broad Islamic government, Omar put together a group of 50 armed students and began to establish an organization that would bring order and a true Islamic regime.

An Islamic nightmare

When he returned to his childhood province of Kandahar, he gathered around him other jihadi leaders who had despaired of the endless infighting between the warlords at the end of the 1980s. One of those leaders was Abdul Ghani Baradar, the Taliban's political leader who led the return of the movement to power. Mullah Omar's young and ideologically driven fighters managed within a short time to overcome the other groups and warlords in the divided country and in 1996 took over most of Afghanistan.

The Taliban labeled the new regime they established the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan. They moved quickly to create state mechanisms, government offices, courts, a police force, and secret services. But the Taliban's Islamic dreams transpired to be a nightmare for the residents of the country as the organization ruled every aspect of their lives with a zealous and fanatical Wahabi interpretation of Islam.

The Islamic Emirate ruled until it was ousted by the American invasion in 2001. It's years in power were its first and only experience of holding the reins of power. The Taliban failed in several important aspects, the most significant being its foreign relations. By hosting Al-Qaida, the Taliban brought upon itself the wrath of the United States. On the domestic front, the Taliban's cruel treatment of minorities led large sections of the population to come out against it. They were happy to shelf the yoke of the Taliban when the American forces arrived. But despite its defeat, the Taliban's most important asset remained intact – its ideology and its ability to use its network of religious schools in neighboring Pakistan to train new generations of ideologically driven jihadi fighters – remained intact.

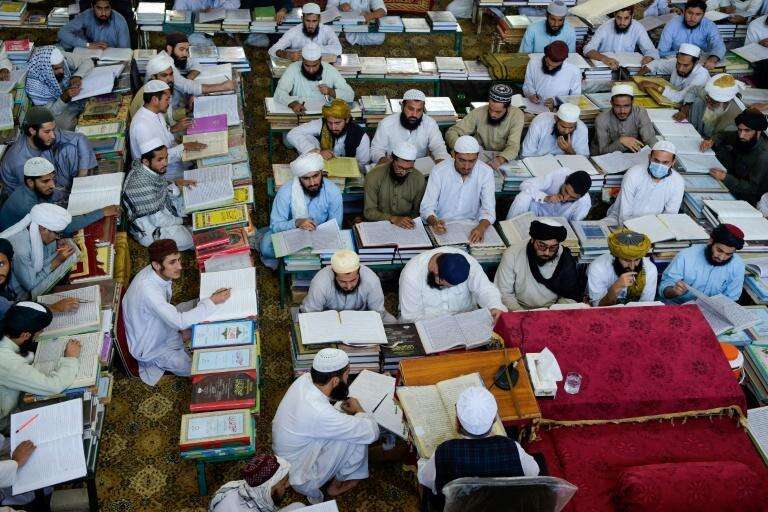

University of Jihad

The Islamic madrasa of Darul Uloom Haqqania sits in a broad valley not far from the town of Peshawar, a Pashtun-majority city in Pakistan with a large Afghan population. The madrassa is similar to other religious institutions in the Islamic world, but this particular religious college is a magnet for the Taliban and its leaders, among them Mullah Omar and Abdul Ghani Baradar who both studied and taught there.

On the face of it, the Deobandi stream of Sunni Islam to which the Haqqania madrassa belongs adheres to the Hanafi school and is not part of the phenomenon of radical political Islam. But with the arrival of the mujahideen in the area in the wake of the war with the Soviet Union, and the deep involvement of Pakistani intelligence in the affairs of the madrassa, the students and teachers became radicalized and introduced elements that had not existed prior to the 1980s.

The radical religious changes that also took place at other madrassas across Pakistan created a new generation of commanders and volunteers for the Taliban, which at least spiritually, was preparing for the return of the Islamic Emirate to power in Afghanistan.

In an item broadcast on French television just over a month ago, the Darul Uloom Haqqania was dubbed the "University of Jihad". The item told the story of Abdul Rasheed, a young Pashtun of Afghan origin who studied at the madrassa and was buried in Pakistan after being killed in a battle with government forces.

"Rasheed sacrificed his life for a great cause," Rasheed's uncle said as he explained the ideology that led his nephew to an early grave. "He went there with a spirit of jihad. Now his young friends want to be martyred like him," he added.

The grieving family expressed even then the hope that the government in Kabul would not last long. "The number of Taliban fighters from Pakistan is much lower than in the past. Now the Afghan Taliban are so numerous they don't need fighters from Pakistan," the boy's uncle said.

Just as in the 1990s, today as well, the winds that blew initially in the Pakistani madrassas, have picked up into a typhoon swapping across neighboring Afghanistan.

Experts believe that the difference between the Taliban of the 1990s and today's organization is at the level of its technical capabilities, while its ideology has remained the same or perhaps even become more radical.

"There is no real difference," says Oreg, regarding the possibility that the organization will once again turn Afghanistan into a sanctuary for terrorist groups. "It's true that we are talking about different people, but the ideology is similar. It is possible they will be hesitant about giving a hand to external groups such as Al Qaida, but that isn't at all certain."

Fearless and uncompromising

Jere Van Dyk, an American journalist and analyst, knows the Taliban better than most Westerners. During the 1980s, as a correspondent for The New York Times, he lived with the mujahideen as they fought the Soviets and the Communist government. He was embedded among the Islamist groups that received support from the United States and the West and became close to the Haqqani network, a tribal group of jihadi warriors named after the madrassa that spouted the Taliban.

In 2008, several years after the fall of the Taliban and several years into the hunt for the Al Qaida leader, Van Dyk went on assignment to the tribal areas of Pakistan where Al Qaida was based to try and figure out what had happened with Osama bin Laden.

Van Dyk tells Israel Hayom in a telephone interview that he was optimistic, but hadn't understood just how much the situation had changed. He paid off local guides to help him get to Al Qaida, but they betrayed him and turned him to the militants, who took him captive. Vans Dyk relates that he was held in captivity for 45 days and at first hadn't realized that he was being held by the Taliban, or by gunmen affiliated with the organization. But as time passed, he realized who his captors were.

During his captivity, Van Dyk was able to observe closely some of the ideological characteristics of the second-generation Taliban. They were merciless ideologists, he tells Israel Hayom. In every conversation, they would tell him, "We are Wahabis and our teachers are Wahabis." In other words, they presented themselves as belonging to one of the most stringent strains of Islam. They want to wipe out the tribal allegiance of Afghani, and in particular Pashtun society, and replace them with allegiance to one tribe - the Islamic nation, he explains.

Van Dyk gives a number of chilling examples of the extent to which his captors were faithful to that idea. One day, he relates, he saw his captors celebrating. It transpired that one of them had killed his brother because he refused to join the organization. The brother preferred to stay loyal to his tribe and family, and this was seen by the Taliban as treachery so grave that it justified his killing.

With another anecdote, Van Dyk explains the difference between the mujahideen that he knew at the end of the 1980s and today's Taliban. When I was in northern Afghanistan with the mujahideen, he recalls, a Russian helicopter passed overhead and the fighters trembled with fear. The Taliban on the other hand, he says, would act as if everything was normal when American drones passed above them. They would even stop to pose for photos with him, when a drone was overhead and could have fired a missile at them at any moment. They were taught for years that a martyr's death is a sanctified goal, he adds.

Van Dyk was freed in a prisoner exchange between his captors and the United States. He was taken to a US base in Jalalabad in the east of Afghanistan. The Taliban, he says, will never agree to a secular government with secular mechanisms inspired by the West, even if all its members are religious. They may, he adds, compromise on certain elements in order to improve relations with certain countries, but they will never give up on their principles.

He recalls that when he was in captivity, a gunman told him that the Taliban would be victorious all the way to Azerbaijan. The comments made it clear to him that the group sees its battle as a global one. It has a global Islamic approach and its ideas will bring a flood of jihadi supporters to wherever the Taliban rules. This, he concludes, is something that will haunt the West for years.

Neta Bar

Source: https://www.israelhayom.com/2021/08/24/afghanistans-merciless-ideologists/

No comments:

Post a Comment