by Brian P. Klein

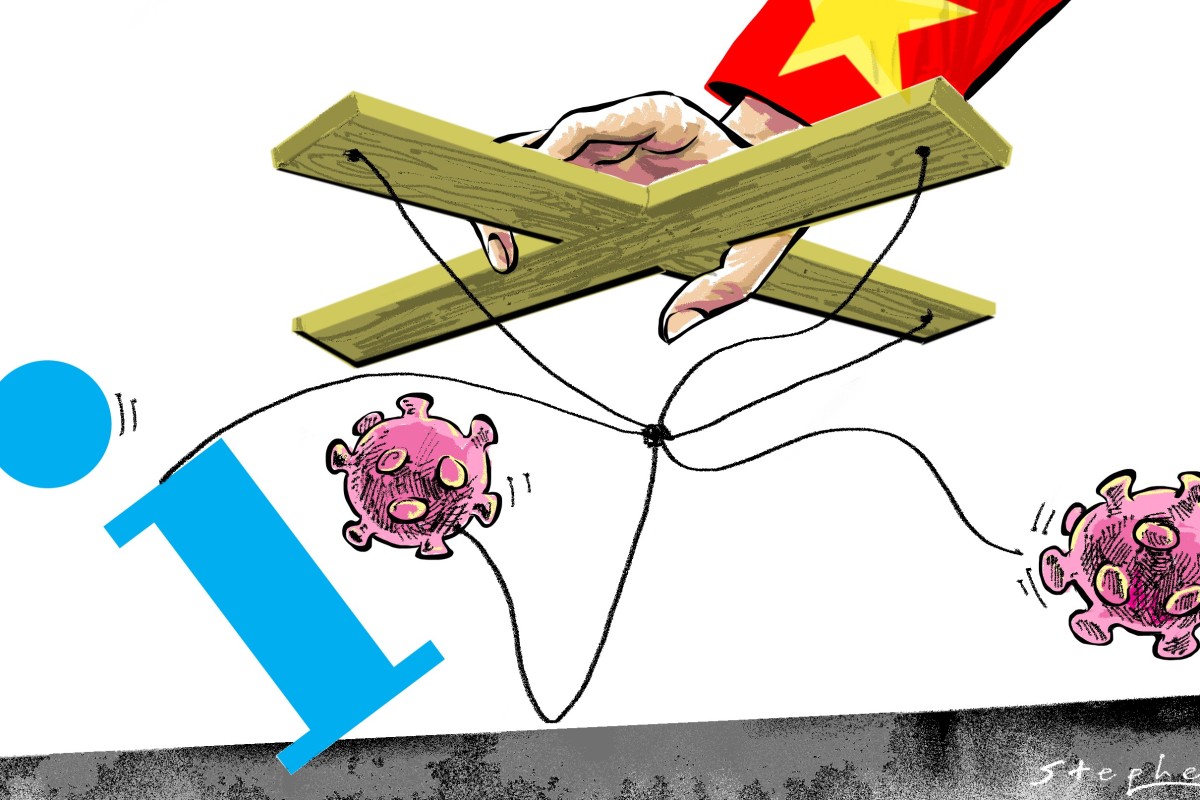

The crisis could have been a turning point in Beijing’s quest to be a reliable world power. Instead, a lack of transparency is poisoning the well of global goodwill and rekindling concerns about China’s influence over the WHO

|

| Illustration: Craig Stephens |

That’s the message coming out of Beijing in a public relations offensive meant to assuage the fears of an increasingly sceptical world.

Serious doubts about the veracity of official Chinese public health data are making it nearly impossible to draw firm conclusions about the scope and scale of the epidemic. Covid-19

infection rates, mortality, recovery, methods of transmission, incubation periods, and even screening methods have all been thrown into doubt. With this lack of confidence will come significant political fallout.

This crisis could have been a major turning point in Beijing’s quest to assume a leadership role in world affairs. Instead, a lack of transparency is poisoning the well of global goodwill and rekindling concerns about China’s control (and manipulation) of information, its influence over the

Source: https://www.scmp.com/comment/opinion/article/3051719/how-china-losing-global-trust-and-goodwill-over-its-handling

Follow Middle East and Terrorism on Twitter

World Health Organisation and its reliability in a crisis.

Take even the most basic data on infection rates, for example. The statistics were already not following the expected exponential trajectory of epidemics and then diagnostic criteria were abruptly changed. That led to a surge of over 15,000 new patients in one day. Then, about a week later, the case definitions were revised again, and the numbers plummeted to barely a few hundred.

What cannot be easily hidden is the spillover effect of the outbreak on the economy. This has turned up the heat on China’s highly politicised disaster response even more.

Brian P. Klein, a former US. diplomat, is the founder and CEO of Decision Analytics, a NYC-based strategic advisory and political risk firm

Medical professionals still can’t seem to agree on whether symptoms, chest images or

blood tests are sufficient diagnostic tools, but two months into the crisis, this is an unexpected problem to encounter, one with dramatic implications for the stemming of the epidemic.

Why so much confusion? There’s been little transparency in the outbreak as information, or even access to it, has been politicised by Beijing.

Ever since the United States airlifted its citizens out of Wuhan, warned against all travel to China, and its airlines stopped service, Beijing has taken umbrage at Washington. Nevertheless, other countries rapidly followed suit with their own evacuations and flight stoppages.

Beijing publicly derided what it called an overreaction on the part of foreign governments. Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi, in a recent Reuters interview, stated: “Everybody can see that the measures taken by those countries go far beyond the recommendations of the WHO.”

These recommendations would include WHO director general Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus’ early statements about avoiding restrictions that “unnecessarily interfere with international travel and trade” – remarks that were especially suspect, however, as China itself imposed increasingly restrictive quarantines throughout much of the country.

China’s information blockade, which has included increased censorship and the

disappearance of citizen journalists who were posting about the Covid-19 outbreak, contributes to the international community’s outsize negative reaction.

Although there are over 75,000 infected patients, physicians are still lamenting how little they know about the disease. Other countries have had to scramble to piece together data from the limited cases they’ve seen first-hand.

After extensive deliberations, the WHO, which has only now been able to send a full delegation to China, finally received permission to visit Wuhan, the epicentre of the outbreak.

Yet, the messaging out of Beijing has shifted: the situation is improving and under control. The Global Times, a state-run media outlet, has called for the resumption of international flights to China. Its editor-in-chief, Hu Xijin, has gone so far as to tweet: “Those who badmouth China’s economy will get a slap in the face.”

Maintaining the perception of stability continues to trump all evidence to the contrary.

China’s political event of the year, the National People’s Congress meeting, is set to be

restart production, Beijing has recently announced that anyone returning to the city must submit to a 14-day quarantine.

Even China’s ally, Russia, has finally decided to close the country to all Chinese nationals in an attempt to stem the spread of the virus (as of February 20, Russia had reported only two cases on its soil).

What cannot be easily hidden is the spillover effect of the outbreak on the economy. This has turned up the heat on China’s highly politicised disaster response even more.

Significant economic contraction, at least in the first quarter of 2020, is all but assured for the

mainland, with hits likely to Hong Kong and Taiwan. Imports and exports are dropping. Global companies are revising down their earnings estimates.

Supply chain vulnerabilities have become more evident in industries from pharmaceuticals to consumer goods and electronics. Factory closures and worker shortages continue.

This type of global disruption is impossible to sweep under the carpet. China’s rise as a reliable global power is in doubt, even as the US under President Donald Trump continues to lose influence.

If the virus doesn’t just shrivel up and die – if, instead, the epidemic truly goes global – China’s instinct to control information will engender scepticism at best and outright scorn at worst.

It is unreasonable to expect nothing less than full-throated public praise for China’s containment efforts. Certainly, no country likes to be criticised, but had China chosen a more cooperative and transparent approach at the outset, it would have engendered more international goodwill and higher levels of support.

This is becoming an increasingly rare commodity as this crisis continues to unfold. Once information is politicised, trust is broken, and without trust there is no leadership.

Source: https://www.scmp.com/comment/opinion/article/3051719/how-china-losing-global-trust-and-goodwill-over-its-handling

Follow Middle East and Terrorism on Twitter

No comments:

Post a Comment