by Gordon G. Chang

Given the capabilities they are amassing, they could, the argument goes, make defiance virtually impossible. The question now is whether the increasingly defiant Chinese people will accept President Xi's all-encompassing vision.

- China's "social credit" system, which will assign every person a constantly updated score based on observed behaviors, is designed to control conduct by giving the ruling Communist Party the ability to administer punishments and hand out rewards. The former deputy director of the State Council's development research center says the system should be administered so that "discredited people become bankrupt".

- Officials prevented Liu Hu, a journalist, from taking a flight because he had a low score. According to the Communist Party-controlled Global Times, as of the end of April 2018, authorities had blocked individuals from taking 11.14 million flights and 4.25 million high-speed rail trips.

- Chinese officials are using the lists for determining more than just access to planes and trains. "I can't buy property. My child can't go to a private school," Liu said. "You feel you're being controlled by the list all the time."

- Chinese leaders have long been obsessed with what Jiang Zemin in 1995 called "informatization, automation, and intelligentization," and they are only getting started Given the capabilities they are amassing, they could, the argument goes, make defiance virtually impossible. The question now is whether the increasingly defiant Chinese people will accept President Xi's all-encompassing vision.

China's

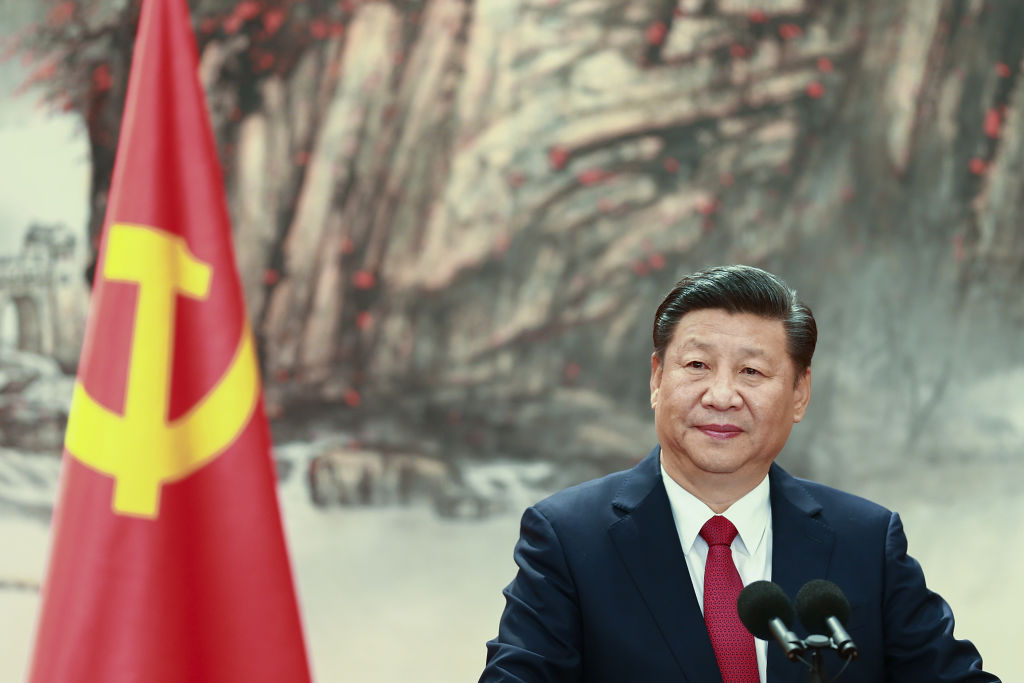

President Xi Jinping is not merely an authoritarian leader. He

evidently believes the Party must have absolute control over society and

he must have absolute control over the Party. He is taking China back

to totalitarianism as he seeks Mao-like control over all aspects of

society. (Photo by Lintao Zhang/Getty Images)

|

By 2020, Chinese officials plan to have about 626 million surveillance cameras operating throughout the country. Those cameras will, among other things, feed information into a national "social credit system."

That system, when it is in place in perhaps two years, will assign to every person in China a constantly updated score based on observed behaviors. For example, an instance of jaywalking, caught by one of those cameras, will result in a reduction in score.

Although officials might hope to reduce jaywalking, they seem to have far more sinister ambitions, such as ensuring conformity to Communist Party political demands. In short, the government looks as if it is determined to create what the Economist called "the world's first digital totalitarian state."

That social credit system, once perfected, will surely be extended to foreign companies and individuals.

At present, there are more than a dozen national blacklists, and about three dozen various localities have been operating experimental social credit scoring systems. Some of those systems have failed miserably. Others, such as the one in Rongcheng in Shandong province, have been considered successful.

In the Rongcheng system, each resident starts with 1,000 points, and, based upon their changing score, are ranked from A+++ to D. The system has affected behavior: incredibly for China, drivers stop for pedestrians at crosswalks.

Drivers stop at crosswalks because residents in that city have, as Foreign Policy reported, "embraced" the social credit system. Some like the system so much that they have set up micro social credit systems in schools, hospitals, and neighborhoods. Social credit systems obviously answer a need for what people in other societies take for granted.

Yet, can what works on a city level be extended across China? As technology advances and data banks are added, the small experimental programs and the national lists will eventually be merged into one countrywide system. The government has already begun to roll out its "Integrated Joint Operations Platform," which aggregates data from various sources such as cameras, identification checks, and "wifi sniffers."

So, what will the end product look like? "It will not be a unified platform where one can type in his or her ID and get a single three-digit score that will decide their lives," Foreign Policy says.

Despite the magazine's assurances, this type of system is precisely what Chinese officials say they want. After all, they tell us the purpose of the initiative is to "allow the trustworthy to roam everywhere under heaven while making it hard for the discredited to take a single step."

That description is not an exaggeration. Officials prevented Liu Hu, a journalist, from taking a flight because he had a low score. The Global Times, a tabloid that belongs to the Communist Party-owned People's Daily, reported that, as of the end of April 2018, authorities had blocked individuals from taking 11.14 million flights and 4.25 million high-speed rail trips.

Chinese officials, however, are using the lists for determining more than just access to planes and trains. "I can't buy property. My child can't go to a private school," Liu said. "You feel you're being controlled by the list all the time."

The system is designed to control conduct by giving the ruling Communist Party the ability to administer punishments and hand out rewards. And the system could end up being unforgiving. Hou Yunchun, a former deputy director of the State Council's development research center, said at a forum in Beijing in May that the social credit system should be administered so that "discredited people become bankrupt". "If we don't increase the cost of being discredited, we are encouraging discredited people to keep at it," Hou said. "That destroys the whole standard."

Not every official has such a vindictive attitude, but it appears that all share the assumption, as the dovish Zhi Zhenfeng of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences said, that "discredited people deserve legal consequences."

President Xi Jinping, the final and perhaps only arbiter in China, has made it clear how he feels about the availability of second chances. "Once untrustworthy, always restricted," the Chinese ruler says.

What happens, then, to a country where only the compliant are allowed to board a plane or be rewarded with discounts for government services? No one quite knows because never before has a government had the ability to constantly assess everyone and then enforce its will. The People's Republic has been more meticulous in keeping files and ranking residents than previous Chinese governments, and computing power and artificial intelligence are now giving China's officials extraordinary capabilities.

Beijing is almost certain to extend the social credit system, which has roots in attempts to control domestic enterprises, to foreign companies. Let us remember that Chinese leaders this year have taken on the world's travel industry by forcing hotel chains and airlines to show Taiwan as part of the People's Republic of China, so they have demonstrated determination to intimidate and punish. Once the social credit system is up and running, it would be a small step to include non-Chinese into that system, extending Xi's tech-fueled totalitarianism to the entire world.

The dominant narrative in the world's liberal democracies is that tech favors totalitarianism. It is certainly true that, unrestrained by privacy concerns, hardline regimes are better able to collect, analyze, and use data, which could provide a decisive edge in applying artificial intelligence A democratic government may be able to compile a no-fly list, but none could ever come close to implementing Xi Jinping's vision of a social credit system.

Chinese leaders have long been obsessed with what then-President Jiang Zemin in 1995 called "informatization, automation, and intelligentization," and they are only getting started. Given the capabilities they are amassing, they could, the argument goes, make defiance virtually impossible.

Technology might even make liberal democracy and free-markets "obsolete" writes Yuval Noah Harari of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem in the Atlantic. "The main handicap of authoritarian regimes in the 20th century — the desire to concentrate all information and power in one place — may become their decisive advantage in the 21st century," he writes.

There is no question that technology empowers China's one-party state to repress people effectively. Exhibit A for this proposition is, of course, the country's social credit system.

Yet China's communists will probably overreach. The country's experience so far with social credit systems suggests that officials are their own worst enemies. An early experiment to build such a system in Suining county in Jiangsu province was a failure:

"Both residents and state media blasted it for its seemingly unfair and arbitrary criteria, with one state-run newspaper comparing the system to the 'good citizen' certificates issued by Japan during its wartime occupation of China."The Rongcheng system has been more successful because its scope has been relatively modest.

Xi Jinping will not be as restrained as Rongcheng's officials. He evidently believes the Party must have absolute control over society and he must have absolute control over the Party. It is simply inconceivable that he will not include in the national social credit system, when it is stitched together, political criteria. Already Chinese officials are trying to use artificial intelligence to predict anti-Party behavior.

Xi Jinping is not merely an authoritarian leader, as it is often said. He is taking China back to totalitarianism as he seeks Mao-like control over all aspects of society.

The question now is whether the increasingly defiant Chinese people will accept Xi's all-encompassing vision. In recent months, many have taken to the streets: truck drivers striking over costs and fees, army veterans marching for pensions, investors blocking government offices to get money back from fraudsters, Muslims surrounding mosques to stop demolition, and parents protesting the scourge of adulterated vaccines, among others. Chinese leaders obviously think their social credit system will stop these and other expressions of discontent.

Let us hope that China's people are not in fact discouraged. Given the breadth of the Communist Party's ambitions, everyone, Chinese or not, has a stake in seeing that Beijing's digital totalitarianism fails.

- Follow Gordon G. Chang on Twitter

Gordon G. Chang is the author of "The Coming Collapse of China" and a Gatestone Institute Distinguished Senior Fellow.

Source: https://www.gatestoneinstitute.org/12988/china-social-credit-system

Follow Middle East and Terrorism on Twitter

No comments:

Post a Comment